One of my most enjoyable volunteer jobs was that of newsletter editor for the New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists from 2009-2015. Beginning with my first issue each month included a page titled “Members from the Past” where I placed an archival image of a NYC organist and asked the membership to identify it. The following month I would list the names of the members who correctly identified the mystery member, together with brief identifying commentary. I tried to include a balance of living and deceased persons. Occasionally I also included Members from the Past in tandem with notifications of chapter programs featuring the mystery member, or birthday commemorations, or some other AGO newsworthy item.

Included here are only New York organists who have died, and in some cases I suspect their inclusion may, in fact, be their only presence on the internet and its related search engines.

These are not meant to be definitive encyclopedia types of entries. In some instances exact dates of birth and death are not known. Rather, they are thumbnail sketches and reminescences for the edification and amusement of our member readers. However, each entry was proof read by several of our chapter editorial board, and is accurate so far as our collective memories can ascertain. In a couple of instances entries are written by chapter members other than myself in which case the author is clearly identified.

One of the hoped for benefits of this enterprise has been commentary and questions from within and without our organization, and these sketchs have been edited to include commentary from our members and others, and I would welcome similar commentary here, whether in the form of additional information, clarification, or (I hope not too often) correction. Complete issues of the newsletters are archived at http://www.nycago.org/html/newsletter.html

Copyright 2015 © Neal Campbell

Jack H. Ossewaarde (1918-2004)

The photo of Jack Ossewaarde at the console of the organ in Calvary Church was scanned from the March 1951 issue of The Diapason together with an article about a program at Calvary Church featuring the music of Henry Wellington Greatorex, a 19th century organist of Calvary. Jack went to Calvary in 1947 (following Harold Friedell when HF went to St. Bartholomew’s) and he stayed there until he left for Houston in 1953 to be Organist and Choirmaster of Christ Church Cathedral and organist and program annotator of the Houston Symphony Orchestra under Leopold Stowkowski.

When Friedell died in 1958, the Rev. Terence J. Finlay, Rector of St. Bartholomew’s, called Ossewaarde to succeed Friedell again, and he stayed at St. Bartholomew’s for 24 years until he retired in 1982. He lived in Stamford, Conn., and was the conductor of the Greenwich Choral Society for several years early in his New York tenure. In his retirement he substituted for several local churches, including Christ’s Church in Rye, New York, and Saint Luke’s Parish in Darien, Conn., and assisted senior citizens in the preparation of their income tax returns.

Jessie Craig Adam

The photo appeared in the June 1932 issue of The Diapason together with an article describing the music program and new organ at Church of the Ascension where she was Organist and Music Director.

Jessie Craig Adam succeeded Richard Henry Warren at Ascension in 1914 and was followed by Vernon de Tar in 1939. She was one of several women who held prominent positions in New York churches during the first half of the 20th century. She was responsible for a large program that included weekly oratorios and the installation of the sizable Skinner Organ, portions of which remain in the present Holtkamp organ.

Robert S. Baker (1916-2005)

The photo was taken in 1939 on a Hammond organ at Interlochen summer music camp in Michigan. Dr. Baker was a graduate of Illinois Wesleyan University and earned Master’s and Doctor’s degrees from the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary, studying with Clarence Dickinson. He was at various times organist of the First Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, Temple Emanu-El in New York, and First Presbyterian Church in New York. He was the founding Director, in 1973, of the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale University. Prior to that he was the Dean of the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary from 1961-73. He was an early proponent of the Hammond organ and wrote his Master’s thesis at Union in 1940 on its evolution and technical properties.

The photo was taken in 1939 on a Hammond organ at Interlochen summer music camp in Michigan. Dr. Baker was a graduate of Illinois Wesleyan University and earned Master’s and Doctor’s degrees from the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary, studying with Clarence Dickinson. He was at various times organist of the First Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church, Temple Emanu-El in New York, and First Presbyterian Church in New York. He was the founding Director, in 1973, of the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale University. Prior to that he was the Dean of the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary from 1961-73. He was an early proponent of the Hammond organ and wrote his Master’s thesis at Union in 1940 on its evolution and technical properties.

Norman Coke-Jephcott (1893-1962)

Dr. Coke-Jephcott was born in England, and won the Turpin Prize when he gained the F.R.C.O. in 1911. He also held F.A.G.O., F.R.C.C.O., and F.T.C.L. diplomas, and was awarded an honorary D.Mus. from Ripon College in 1945.

He came to the United States in 1911 to be the organist of the Church of the Holy Cross in Kingston, New York, leaving there in 1915 to take up a position at Church of the Messiah in Rhinebeck. He served there until he became organist of Grace Church in Utica in 1923, staying there until he was called to New York to be Organist and Master of the Choristers at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine in 1932. He retired from the cathedral in 1953, but stayed in New York, teaching privately and playing at St. Philip’s Church in Harlem. For many years he was on the National Examinations Committee of the AGO.

This photo was taken in the late 1950s at Coke-Jephcott’s home “Blue Gates” in upstate New York by the late Charles Hizette, a pupil of “Cokey” and is provided through the courtesy of Earle Grover.

Roberta Bitgood (1908–2007)

The photograph appeared in the June 1932 issue of The Diapason announcing her new position at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Miss Bitgood graduated from Connecticut College where she studied with J. Lawrence Erb before coming to New York to study at the Guilmant Organ School as a student of William C. Carl. She earned the A.A.G.O. and F.A.G.O. certificates while a student at the Guilmant School. Later, she earned the S.M.M. and S.M.D. degrees at Union Theological Seminary School of Sacred Music. While in New York she assisted Dr. Carl at First Presbyterian Church in New York directing the junior choir and the mixed glee club and playing for the Sunday School and weekday noon hour services. Later she was the director of music at First Moravian Church in New York where she was introduced to the musical heritage of that denomination and ultimately wrote her UTS thesis on Moravian Music.

The photograph appeared in the June 1932 issue of The Diapason announcing her new position at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Miss Bitgood graduated from Connecticut College where she studied with J. Lawrence Erb before coming to New York to study at the Guilmant Organ School as a student of William C. Carl. She earned the A.A.G.O. and F.A.G.O. certificates while a student at the Guilmant School. Later, she earned the S.M.M. and S.M.D. degrees at Union Theological Seminary School of Sacred Music. While in New York she assisted Dr. Carl at First Presbyterian Church in New York directing the junior choir and the mixed glee club and playing for the Sunday School and weekday noon hour services. Later she was the director of music at First Moravian Church in New York where she was introduced to the musical heritage of that denomination and ultimately wrote her UTS thesis on Moravian Music.

After leaving the metropolitan area Dr. Bitgood held positions in Buffalo, New York; Riverside, California; and Bay City, Michigan, and traveled extensively on behalf of the Guild in various positions she held. In 1975 Roberta Bitgood made AGO history as the first woman and the first write-in candidate to be elected president. She was a prolific composer and her anthems and solos are still well represented in the repertorie of churches around the coutnry.

In her “retirement” Roberta moved home to Connecticut and served as dean of the New London County AGO Chapter and as organist and choir director of the Waterford United Presbyterian Church.

Andrew Tietjen (1910-1953)

Andrew Tietjen in the churchyard of Trinity Church. Photo courtesy of Yolande Tietjen Fitz-Gerald, Rowayton, Connecticut.

Tietjen was a legendary organist and choirmaster in his own time who died prematurely young from complications of a misdiagnosed disease contracted while serving in World War II. At the time of his death he was the associate organist of Trinity Church Wall Street, and was the founding director of the Trinity Choir of St. Paul’s Chapel, a choir formed in 1947 specifically for weekly Sunday broadcasts on CBS from St. Paul’s Chapel. Before World War II he played a series of Sunday morning organ recitals broadcast weekly on CBS from Chapel of the Intercession for which he was selected from among several organists, including E. Power Biggs, who auditioned for the job. Young Andrew began his career as a choirboy and pupil of T. Tertius Noble at St. Thomas Church and Choir School, where he assumed the duties of assistant organist at the age of 15, and was playing preludes, postludes, and weddings before that. He was generally considered one of Noble’s most brilliant pupils, together with Paul Callaway and Grover Oberle. Tietjen later went on to serve at St. Thomas Chapel (now All Saints Church), All Angels Church, Chapel of the Intercession, and Trinity Church-St. Paul’s Chapel. At Trinity-St. Paul’s he played four recitals weekly–two at Trinity and two at St Paul’s, in addition to the weekly broadcast. As was common at the time, he held no academic degrees, but earned the FAGO and FTCL certificates. He studied at Trinity School and Columbia University, where Daniel Gregory Mason arranged for him to audit his classes.

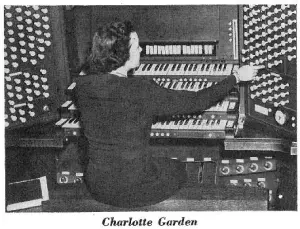

Charlotte Garden

Remembered only by a few today, Charlotte Garden was one of America’s most famous recitalists and teachers in the 1950s and ’60s. As a teacher at the Union Theological Seminary School of Sacred Music she had a huge impact on students. In his “Dear Diary” article in the May 2010 issue of The Diapason Charles Huddleston Heaton tells of his pligrimages to her church, Crescent Avenue Presbyterian in Plainfield, N. J., a church of cathedral proportions and an organ to match. The photo above, which was scanned from the 1956 NYC AGO National Convention booklet, shows Dr. Garden at the console of the church’s Richard Whitelegg/M. P. Moller organ.

At her recital in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for the 1956 convention she played the first performance of Alec Wyton’s Fanfare for the State Trumpet which was written for the occasion. The work was later published by H. W. Gray and titled simply Fanfare and is inscribed “To G. Donald Harrison, who created the State Trumpet.” GDH later said that it was the only piece ever dedicated to him.

At the age of 53 Charlotte Garden died in an automobile accident on May 19, 1961. She was a passenger in the car driven by the tenor soloist of her church who survived. They were en route to a concert at the Bethlehem Bach Festival. Robert Baker played for her funeral at Crescent Avenue where she had been organist for over 30 years.

Born Charlotte Mathewson in Hartford, she spent her youth in North Carolina, where she became a church organist at age 11, and Richmond, Virginia (where her sister Mary Ann Gray is still alive and playing for church) . She was a graduate of Salem College and Union Theological Seminary School of Sacred Music where she studied with Clarence Dickinson. She also studied with Widor in Paris and Ramin in Leipzig. She held an honorary doctorate from the College of the Ozarks. She was the first woman admitted to the Bernard LaBerge management, and she concertized and taught extensively. As a composer and arranger many of her works were widely used at the time. She was also a consultant for the new organ at Philharmonic Hall at Lincoln Center.

James Morris Helfenstein (1865-1953)

Organist and Master of the Choir of Grace Church from 1894-1922, Helfenstein was the founder of the church’s Choir of Men and Boys and was the founding Headmaster of the Grace Church Choir School. This was the first choir school in New York and was the prototype for those established later at St. Thomas Church and the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine.

Organist and Master of the Choir of Grace Church from 1894-1922, Helfenstein was the founder of the church’s Choir of Men and Boys and was the founding Headmaster of the Grace Church Choir School. This was the first choir school in New York and was the prototype for those established later at St. Thomas Church and the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine.

Helfenstein had an unlikely background for a church musician. A member of a prominent New York family which descended from Gouverneur Morris (one of the foremost statesmen of the American Revolution who was also in the Continental Congress and Minister to France) he graduated from Yale and Columbia University Law School and held a seat on the New York Stock Exchange. But he was always passionate about church music and frequently traveled to England to observe cathedral and academic choirs there. He came to Grace Church having previously established a similar choir at All Angels Church.

In 1922 in a serious dispute with a member of the vestry of Grace Church over the running of the choir school, he resigned suddenly, and subsequently became Organist and Choirmaster of the Church of the Heavenly Rest.

The NYC Chapter’s annual Presidents’ Day Conference in February 2011, held at St. Bartholomew’s Church, was titled “The Grand Old Men” and it consisted of presentations on the lives and music of Clarence Dickinson, Harold Friedell, Seth Bingham, and T. Tertius Noble, each prominent New York organists and composers in the first half of the 20th Century. In the months leading up to the conference, as a way of promotion, I ran photos and very brief commentary on each of them, leaving substantive information for the individual presentations on Presidents’ Day.

Clarence Dickinson ( 1873- 1969)

Of course we know Dickinson as one of the founding members of the AGO, the founder of the School of Sacred Music at Union Theological Seminary, and the organist of the Brick Church for over fifty years. The photo at right is from 1920, scanned from The American Organist. Dickinson’s life and music was discussed by Lorenz Maycher and his comprehensive handout containing several historic photographs is available at the link below: http://www.nycago.org/pdf/110221_Dickinson_Maycher.pdf

Harold Friedell (1905-1958)

The photograph shows HF in his early 20s from a newspaper notice of an upcoming recital at the First Methodist Church in Jamaica, Queens, his family church where he was organist in his teens. My handout, consisting of a biographical time line, bibliography and sources, discography, and catalog of Friedell’s complete works may be found at the link below, and my article written on the occasion of HF’s 100th anniversary is contained elsewhere on this site: http://www.nycago.org/pdf/110221_Friedell_Campbell.pdf

Seth Bingham (1882-1972)

Bingham was the organist of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church and he taught at Columbia University. Christopher Marks’talk focused solely on the organ works of Seth Bingham, and his handout, which included not only a complete list of Bingham’s organ works, but the persons to whom each work is dedicated, provides a snapshot into the lines of continuity in the organ community of the day. It may be found at the link below: http://www.nycago.org/pdf/110221_Bingham_Marks.pdf

T. Tertius Noble (1867-1953)

The final of the four grand old men to be discussed was T. Tertius Noble, the founder of the St. Thomas Choir School, and organist of St. Thomas Church. It was led by John Scott, Dr. Noble’s successor three times removed. John’s talk was based primarily on Noble’s unpublished autiobiography contained in the AGO Organ Library at Boston University http://www.organlibrary.org/ However, from the archives of St. Thomas Church, Dr. Scott unearthed several fascinating letters to and from Noble from some of the leading figures in church music of the day from his native England. The ones used for the lecture may be found at the link below: http://www.nycago.org/pdf/110221_Noble_Scott.pdf

The Presidents’ Day Conference concluded with Evensong sung by the Choir of St. Bartholomew’s Church directed by William Trafka, accompanied by Paolo Bordignon, featuring the music of these four New York organist-composers.

Participants in the NYC AGO Presidents’ Day Conference 2011 on the Chancel steps with the Choir of St. Bartholomew’s Church. Photo by Steve Lawson.

Lilian Carpenter (1889-1973)

(1889-1973)

Rollin Smith, one of the chapter members who correctly identified Miss Carpenter provided the following biographical sketch:

Lilian Carpenter was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 10, 1889. Coming to New York, she studied with Gaston Dethier at the Institute of Musical Art and was the first to graduate with an artist diploma in organ. She was his assistant, teaching organ and piano at the Institute for 30 years; the school eventually became the Juilliard School and once Vernon de Tar got in as organ teacher by default (both David McK. Williams and E. Power Biggs were hired but never showed up), he eased her out.

Lilian Carpenter was the first woman to earn the F.A.G.O. diploma and was always active in the Guild, including serving as national treasurer. She was organist of the Church of the Comforter-Reformed; Flatbush Presbyterian; and Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn and, at the time of her death, Edgehill Church in Riverdale. She died on February 21, 1973.

Arthur Sewall Hyde

Hyde was the organist of St. Bartholomew’s Church from 1908-1920, studied with Widor in Paris, and came to St. Bartholomew’s from Emmanuel Church in Boston where he served with the Rev. Leighton Parks, before Parks was called to St. Bartholomew’s. It was Parks who, upon assuming the Rectorship of St. Bartholomew’s, went to England looking for an organist, someone not too British as legend has it. It’s never been fully explained why Parks was looking in England if he didn’t want someone too British! But he found what he was looking for in Leopold Stokowski who came to America as the organist of St. Bartholomew’s from 1905-08. Following Stokowski’s brief and colorful tenure, it seems Dr. Parks looked to someone familiar in calling his old Boston organist to join him in New York.

Hyde was greatly loved by the choir and congregation. He volunteered for service in World War I, but when he returned he never fully recovered from the strain and injuries he sustained, and his death in 1920 was lamented by all. A concert was given in his memory, the proceeds of which were used to install chimes in the organ. A large tablet above the lectern reads:

The Chimes in this Organ

Are the Gift of the Choir

In Memory of Arthur Sewall Hyde

Organist and Choirmaster 1908 – 1920

Artist Soldier Christian

M. Searle Wright

Within hours of posting Searle Wright’s photographas the Member from the Past, many chapter members correctly identified this icon of our profession. This early photo of Wright is courtesy of Andrew Kotylo, associate organist of Trinity-on-the-Green in New Haven, who has researched the life and works of Searle Wright for his Doctor of Music dissertation at Indiana University and he provided the following synopsis:

Within hours of posting Searle Wright’s photographas the Member from the Past, many chapter members correctly identified this icon of our profession. This early photo of Wright is courtesy of Andrew Kotylo, associate organist of Trinity-on-the-Green in New Haven, who has researched the life and works of Searle Wright for his Doctor of Music dissertation at Indiana University and he provided the following synopsis:

Searle Wright (1918-2004) was Director of Chapel Music at St. Paul’s Chapel, Columbia University from 1952 until 1971. Wright’s residency in New York began in 1936 when he became a “resident pupil” of T. Tertius Noble at St. Thomas Church. Almost instantly, he began a close connection with the local AGO, first through the now-defunct Headquarters Chapter and then as a founding member of the New York City Chapter in 1951. One might be hard-pressed to find someone who contributed as much in serving the Guild as Wright did during his New York years. As a member of the National Council, he held tenures as Secretary, Librarian, and finally as President; served on countless committees and panels; and co-originated the National Playing Competition and encouraged the development of the Improvisation Competition.

The festival concerts that Wright conducted at St. Paul’s Chapel were truly legendary. Three times each year, he would present comprehensive programs featuring the latest choral and instrumental works of Vaughan Williams, Holst, Dello Joio, and others–several of which were American, if not world premieres. Wright’s international renown was also spread through his fine sacred choral and organ compositions, his long tenure as a teacher of improvisation and composition at Union Seminary, and his uncanny versatility as an organist which earned him equal respect from his theatre and classical organist colleagues–and also enabled him to build bridges of understanding between these two camps who had formerly looked upon each other with disdain. In spite of his wide-ranging successes, Wright forever remained the epitome of kindness and humility, and with his refined wit and manner of dress, was a class act and true gentleman.

Philip James (1890-1975)

Philip James, at work on the score of “Fanfare and Ceremonial” for band. Photographed by B. Perry, Aug 16, 1955, Francestown, New Hampshire. From “A Catalog of the Music Works of Philip James” comp. Helga James, 1981.

James was born in Jersey City, N. J., and was educated in New York public schools and at the College of the City of New York. His teachers include J. Warren Andrews, Alexandre Guilmant and Joseph Bonnet in organ and Rubin Goldmark and Rosario Scalero in composition. He was the organist for several churches in New York and New Jersey (St. John’s Jersey City: St. Luke’s Montclair; St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowerie. NYC) but he is primarily remembered as a composer, conductor, and teacher at Columbia University and New York University, where he was head of the music department. He appeared as guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic, National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, and the NBC and CBS orchestras. He was the music director of radio station WOR, and was the regular conductor of the New Jersey Orchestra, Brooklyn Orchestral Society, and was the music director of theatrical productions by Winthrop Ames and Victor Herbert. In 1932 he won the $5,000 First Prize of the National Broadcasting Orchestral Awards for Station WGZBX, an orchestral suite, which was performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Rochester Philharmonic, and the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski. The following year he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He was also a member of the Century Association and the MacDowell Colony. His anthem By the waters of Babylon, a dramatic setting of Psalm 137 was at one time de rigeur in the repertoire of most church choirs and it was recorded and performed by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. On May 17, 1970, the Church of St. Mary the Virgin marked the occasion of his 80th birthday with a recital of his works played by Rollin Smith and the choir sang his Magnificat and Nunc dimittis, Come Holy Spirit, and O Saving Victim at Evensong and Benediction directed by James Palsgrove with McNeil Robinson as organist.

Marie Schumacher (1923-1979)

(1923-1979)

Marie Schumacher was a student and disciple of Ernest White whom she also assisted during his celebrated tenure at the Church of St Mary the Virgin. She later married the Rev. Frederick William Blatz (1910-1962), an Episcopal clergyman, and served at St. Paul’s Church in Westfield, New Jersey, and at churches in upstate New York and Washington, D. C., where she oversaw the installation of organs designed by Ernest White in his unique style. She also studied with Virgil Fox at the Peabody Conservatory.

The photo at the right was published in March 1949 issue of T. Scott Buhrman’s The American Organist (no relation to the present AGO magazine of the same name) with a caption in his inimitable curmudgeonly style:

“Marie Schumacher, whose ability, not to mention also courage, has placed her on the organbench of that highest of high churches in spite of the unwritten ecclesiastical law that tries to exclude women from these holy precincts–and she holds her own with the best of them all.”

David McK. Williams (1887-1978)

David McK. Williams in his Canadian Army uniform in 1920.

David McKinley Williams was born in Wales he came to Denver at an early age and was trained as a chorister by Henry Housley at the Cathedral of St. John in the Wilderness. At age 13 he became organsit and choirmaster of St. Peter’s Church in Denver. In 1908 he came to New York as organist of Grace Church Chapel and studied with Clement Gale. He spent the years from 1911 to 1914 in Paris where he studied with Vierne, D’Indy, and Widor. Returning to New York, he was at the Church of the Holy Communion from 1914 to 1916, when he joined the Canadian Artillery and saw service overseas. In 1920 he returned to Church of the Holy Communion, leaving six months later to become organist and choirmaster of St. Bartholomew’s Church upon the death of Arthur Hyde. There, for the next twenty-seven years, he developed an already outstanding program into one of tremendous popularity and superlative influence. Inspired by the organ in the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, it was his vision that led to the placing of the Celestial Organ in the new dome of St. Bartholomew’s Church in 1930 and by all accounts he was very creative in his service playing and accompanying. He was precise and demanding of his choir and was vivid and dramatic in his music and in his speaking. Virgil Fox was a great admirer of David McK. Williams and quotes him at some length in his 1968 masterclasses, recordings of which are extant and may be found at http://www.virgilfoxlegacy.com/masterclass.html In fact, much of Fox’s own theatrics are the result of his infatuation with DMcKW, including his wearing of a cape! After his retirement from St. Bartholomew’s he traveled widely and maintained many friendships throughout the country with students, colleagues, and others, including James Michener, with whom he traveled to the South Pacific.

He died in 1978 and is buried in the crypt of St. Bartholomew’s Church.

The Choir of St. Bartholomew’s Church in the 1940s. DMcKW is at the altar end of the first row on the right side.

Pietro Yon (1886-1943)

Yon at St. Francis Xavier, New York, in 1919

Yon was born in Italy and studied at the Royal Conservatory in Milan, the Conservatory in Turin, and graduated from the Academy of St Cecilia in Rome. Before coming to America he was an assistant organist of the Basilica of St. Peter in Vatican City. He was organist of St. Francis Xavier in New York from 1907-19, and again from 1921-26, before assuming his position at St. Patrick’s Cathedral where he remained until his death in 1943. He was also an honorary organist of St. Peter’s at the Vatican.

Roberta Bailey

Chapter member Craig Whitney, author of All The Stops: The Glorious Pipe Organ And Its American Masters, and former managing editor of The New York Times, correctly identified this entry and provided the following sketch of Miss Bailey’s very interesting life and career:

After graduating from the University of Minnesota where she studied music and journalism-advertising, Roberta Bailey came to New York in September of 1949 as assistant to Virgil Fox at Riverside Church. Besides playing the organ (then a Hook & Hastings that Fox wanted to replace) her duties included climbing into the organ chamber to pull out ciphering pipes and chauffeuring Virgil around in his white Cadillac convertible, and in 1951 she became his concert manager. She found him demanding, and “selfish,” but in a class of his own. In 1955, thanks to continuing ciphers and to the generosity of John D. Rockefeller Jr., Aeolian-Skinner completed installation of the new organ.

In 1956 the AGO National Convention was to be in New York and Virgil Fox and Robert Baker were the co-chairs of the convention. Roberta Bailey was the convention manager, and she had Fox play the American premiere of Durufle’s Suite, op. 5, dedicating the performance to the memory of G. Donald Harrison, who had died two weeks earlier.

Soon after the convention, she met and fell in love with Richard F. Johnson, a businessman who was also an organist in Westborough, Massachusetts, and after they were married she moved there and had three children. Roberta Bailey Concert Management tried to carry on as Fox’s concert manager from Massachusetts, but in 1963 Fox replaced Bailey with Richard Torrence, who had become his personal secretary.

Her concert management business continued successfully, with Pierre Cochereau and Karl Richter among her famous clients, but in 1973, when Fox was trying to acquire the Hammond Castle Museum in Gloucester, Mass., she and Johnson decided to help him raise money and convince local authorities and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese in Boston, which owned the museum, to let him buy it. When they did, in 1975, she and Johnson served as directors of the Hammond Castle Museum and of the Virgil Fox Center for the Performing Arts he established there. His ambitions to enlarge the organ that the inventor John Hays Hammond Jr. had installed in the castle, and to broaden the cultural ambitions of the museum produced immediate financial disaster, and Fox forced Bailey and Johnson to resign after only a few months.

Roberta Bailey Johnson died in 1996, before she could complete a planned autobiography. Richard Johnson died in 2001.

Ernest Mitchell (1890-1966)

Mitchell was the organist and choirmaster of Grace Church in New York from 1922-1960. The photograph of Mitchell at right was cropped from a choir photo taken in 1934. Many organists “of a certain age” however will likely have seen the photo of him below which appeared in several 1950s-60s era editions of the World Book Encyclopedia with the entry on ORGAN. The curious caption no doubt refers to Mitchell’s very precise instructions for the console of the new 1928 Skinner organ in Grace Church. It was lavish in its appointments and controls, was very compact and low for so large an organ and was the prototype for the even larger 1948 console Aeolian-Skinner built for The Riverside Church. The console is on display in the music office of Grace Church.

Mitchell was the organist and choirmaster of Grace Church in New York from 1922-1960. The photograph of Mitchell at right was cropped from a choir photo taken in 1934. Many organists “of a certain age” however will likely have seen the photo of him below which appeared in several 1950s-60s era editions of the World Book Encyclopedia with the entry on ORGAN. The curious caption no doubt refers to Mitchell’s very precise instructions for the console of the new 1928 Skinner organ in Grace Church. It was lavish in its appointments and controls, was very compact and low for so large an organ and was the prototype for the even larger 1948 console Aeolian-Skinner built for The Riverside Church. The console is on display in the music office of Grace Church.

Mitchell was a legend in his own day. He came to Grace Church from Trinity Church in Boston and he knew many of the leading organists in Europe and often played the first American performances of their works as voluntaries and recital pieces at Grace Church. Both Tournemire and Vierne dedicated works to him. In a letter to me dated 14 June 2002 Jack Ossewaarde said “David McK. Williams said that he [Mitchell] was the most brilliant of the organists in New York during his [1920-46] heyday.”

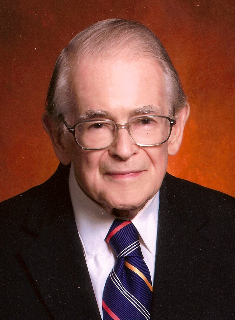

Warner Hawkins

Warner Hawkins, Mus.D., F.A.G.O.

Several members incorrectly identified this mystery member as Clarence Dickinson, and the resemblance is remarkable. Dickinson, in an early photograph, was the mystery member in the October 2010 issue. For comparison photographs of Dickinson in his later years, see Lorenz Maycher’s comprehensive handouts from his 2011 Presidents’ Day presentation.

However, Warner Hawkins was the correct identification, and the photo at right was taken from his obituary notice in the April 1960 issue of The Diapason.

Hawkins was National Warden of the AGO, as the office was then known, from 1941-43. The name was later changed to President. He was a student of Gaston Dethier at Juilliard, on whose staff he served for ten years before becoming head of the music department at the College of New Rochelle, New York. He later became associate director of the New York College of Music and was organist of Christ Church (Methodist) for twenty years. His funeral was held at Christ Church and its pastor and one time national chaplain to the AGO, Dr. Ralph Sockman, presided.

Claire Coci (1912-1978)

Claire Coci at the console of the organ in the West Point Cadet Chapel in the 1940s.

Haig Mardirosian, Dean of the College of Arts and Letters at the University of Tampa, writes the following about Miss Coci:

Claire Coci was one of those organists who enjoyed a larger-than-life presence in the profession through the 1950’s Although a recitalist since the late 1930’s, her career advanced the most rapidly after marrying Bernard LaBerge, the impresario and manager who died in the early 1950’s (his secretary, Lillian Murtagh took over the business which continues today as Karen McFarlane Concert Artists). Coci remarried in the later 1950’s and shortly thereafter moved to Tenafly, NJ where she established her own music school, the American Academy of Music in an old Victorian house on Magnolia Avenue.

Mainly a recitalist, Coci was a product of the virtuoso tradition and studied with Charles Courboin and Marcel Dupré. While she was best remembered for her virtuoso accouterments, colorful costume, and a Plexiglass organ bench, Coci also invested much effort in playing the works of contemporary composers. She had, however, a performer’s ego. Like Virgil Fox, she called herself “Dr.” after receiving an honorary degree. She also hesitated little in making particular claims of prominence. She greeted a young auditioning student in 1960 in Tenafly by springing to her feet from her desk (on which she had previously planted her feet while on a phone call) in front of a map with pins marking all of her recital destinations and saying “you are now looking at the world’s greatest woman organist!”

Despite this, Coci was not an elitist. She took advantage of all playing and teaching opportunities from the greatest of venues in Europe and the US to an appearance at the local high school in her town of Tenafly with the community orchestra in a Haydn concerto on a small Allen organ.

Edward Linzel

Edward Linzel (1925-2010)

Kyle Babin, a former member of our chapter who is the organist of Grace Church in Alexandria, Va., and who wrote his doctoral dissertation at Manhattan School of Music on the history and music of the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, writes the following:

Edward Linzel was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, on September 14, 1925. From an early age, he showed a vested interest in music, especially the organ. While a student at Westminster Choir College in 1945, he first met Ernest White at a recital played by White at Princeton University Chapel. He subsequently moved to New York City to study privately with White while he was Director of Music at the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin. Linzel also studied with White later at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore. Through his connection with Ernest White, Linzel immersed himself in the vibrant music scene at St. Mary’s. In this milieu, he was among several other talented students of White, including Albert Fuller, Marie Schumacher, and Edgar Hilliar. These students, including Linzel, performed in frequent recitals in White’s Studio in the St. Mary’s Parish House.

Linzel also performed as a recitalist in venues across the country, and as a true disciple of Ernest White, he relished in presenting modern organ works, many of which were by Olivier Messiaen. Linzel also substituted for White as an organ teacher at Union Theological Seminary. In October of 1958, Linzel succeeded White as Director of Music at St. Mary’s, and he moved into the Parish House apartment where White had previously resided. One of his notable achievements in this time was his continuation of music publishing under the auspices of “St. Mary’s Press.” Linzel also adapted the chant propers of the Mass into English versions that were far superior to the rather antiquated ones found in the English Gradual. In 1962, Linzel left St. Mary’s and continued to hold a number of church jobs in other cities. At the end of his life, he lived in his hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas, and in his last days, he lived with his son in the Dallas area, where he died of a heart-related illness on January 19, 2010.

Edouard Nies-Berger (1904-2002)

Edouard Nies-Berger and Albert Schweitzer at St. Thomas Church, Strasbourg, 1959.

Edouard Nies-Berger, sometime organist of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and protegé of and collaborator with Albert Schweitzer, was born in Strasbourg in 1903 when that region was still part of the German empire. At 15 he saw the French army reclaim the city and the surrounding provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. In 1922 he came to New York at the age of 19 and remained in the United States professionally for the rest of his life, although he maintained an apartment in Colmar.He played in various churches and synagogues in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. During his Los Angeles years he found work in the movie studios and recorded the organ music for “The Bride of Frankenstein” and “Border Town.” “They had me play Bach’s great Toccata in D minor while Karloff carried Elsa Lancaster to her execution” Nies-Berger told an interviewer for the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 1991. “It was not my proudest moment artistically.”

Nies-Berger aspired to be a conductor, so in 1937 he left the United States for Salzburg where he studied with Bruno Walter and Rudolf Baumgartner. He was preparing for his European conducting debut when the Nazis took over Salzburg. He moved to Riga, Latvia, and from there to Brussels conducting opera and summer concerts. Shortly after Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Nies-Berger caught the last boat out of Rotterdam and returned to New York.

He kept his conducting dream alive for a few years in New York where he founded an orchestra comprised mainly of freelance musicians. These concerts were characterized by progressive programming, often featuring Nies-Berger conducting works for organ and orchestra from the console in Town Hall. He earned the respect of Olin Downes writing in the New York Times. T. Scott Buhrman, writing in The American Organist (no relation to the present day journal of the same name), was particularly effusive in his praise of Nies-Berger’s offerings. “But after renting the halls and paying the stagehands and hiring the musicians, there was no money left. I had married and had a son. It was time to be a responsible father” Nies-Berger acknowledged in the aforementioned interview. In 1940 he moved to Richmond, Virginia, and to relative stability as the organist of Centenary Methodist Church. Attempts to start a symphony orchestra in Richmond had recently failed, and Nies-Berger was frustrated in his attempts to organize musical groups in the city. After only two years, he again returned to New York and began what turned out to be the most fruitful years of his career.

Artur Rodzinski, the new conductor of the New York Philharmonic, tapped Nies-Berger to be the orchestra’s organist, a position he held for several years playing and recording under such conductors as Walter, Szell, Reiner, Stokowski, and a young Leonard Bernstein.

Albert Schweitzer was a family friend when Edouard was growing up in Strasbourg. His father and Schweitzer had been students together at Strasbourg University where they were each disciples of Professor Ernst Munch, leader of the Bach circle, and father of the conductor Charles Munch. By the time Edouard moved to New York in 1942 , Schweitzer was established in his missionary work in Africa. However, Schweitzer made a trip to the United States in 1949 where he and Nies-Berger were reunited. “To meet Schweitzer again after so many years was a wonderful event for me” Nies-Berger recalled.

Their rekindled friendship culminated in a project that cemented Nies-Berger’s and Schweitzer’s association. Schweitzer had collaborated with Widor in a new edition of Bach’s organ works, the first five volumes of which were published by Schirmer before Widor died and before the outbreak of World War II interrupted the project. Schweitzer asked Nies-Berger to be his collaborator in the remaining three volumes which contained the chorale preludes.

“For the next six years, three or four months each summer, I went to Alsace or Africa to work with Schweitzer. He made a little time every day for Bach. It wasn’t easy–he’d won the [Nobel] Peace Prize already, and everybody in the world was after him for one thing or another. He was too kind to say no. To work with Schweitzer was almost like working with Bach. To know him at such close range was the great spiritual experience of my life. I have never thought the same, or made music the same way, after Schweitzer” said Nies-Berger. By the time the project was finished in the 1960s, Schirmer’s Widor-Schweitzer / Nies-Berger edition of Bach’s organ works represented the most current scholarship and was widely used by students and performers.

The demands of professional life in New York became more pressing and Nies-Berger left New York for the last time, as he moved again to Richmond to be the organist and choirmaster of St. Paul’s Church, where he served from 1960 until he retired in 1968. He continued to live in Richmond (and in Colmar) until his death in 2002.

Much of his retirement time was spent writing treatises on music and philosophy, as well as a memoir about his time with Schweitzer. After multiple rejections from American publishers the memoir (written in English, which by now Nies-Berger considered his primary language) was published in 1995 in a French translation titled Albert Schweitzer m’a dit as part of a series Memoire d’Alsace by the small French firm Editions La Nuee Bleue. Rollin Smith has since prepared an English translation published by Pendragon Press. Nies-Berger was also a composer with several published compositions to his credit, one of which, Resurrection: An Easter Fantasy, is still in print in an anthology published by H. W. Gray.

Age 98 in the Richmond Times Dispatch.

William Strickland (1914-1991)

William Strickland, from the program book of the AGO National Convention in New York, 1956.

Strickland was a major player in the musical world of New York in

the first half of the 20th century, and not just within organists’ circles. But it was as an organist that he got his start, first as a chorister at the Cathedral

of St. John the Divine, and later as the organist of Christ Church, Bronxville, and Calvary Church in New York.

He would likely have succeeded David McK. Williams at St. Bartholomew’s Church were it not for the fact that in 1946 he was engaged to be the founding music director of the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, serving there from 1946-51. In Nashville he was known for his imaginative programing which often featured new music by living composers. He steadily improved the professionalism of the group and laid the foundation for the work of some of his better-known successors such as Thor Johnson, Kenneth Schermerhorn, and Leonard Slatkin.

Returning to New York after his tenure in Nashville, he was for a time the conductor of the Oratorio Society of New York. Working with the State Department, he conducted concerts of American music in Europe and the Far East. In 1955 he conducted the inaugural concert in a fund-raising series to preserve Carnegie Hall, and in 1956 he conducted a program for the AGO National Convention in New York. The photo at right is from the program booklet.

Always passionate about contemporary music he edited a series of works for organ by composers who aren’t generally associated as writers for the organ, such as Krenek, Milhaud, Copland, and Harris which were published by H. W. Gray and is still in print as an anthology.

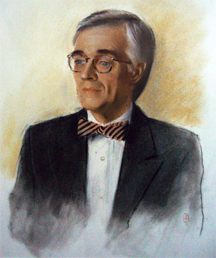

Paul J. Sifler (1911-2001)

Paul J. Sifler

Several members incorrectly identified this Member from the Past as John Grady, and the resemblance is obvious to those who knew John. However, Paul J. Sifler is the correct identity.

Sifler, a naturalized American citizen of Yugoslavian birth, was a prolific composer of organ and choral works, of which his Agony and Despair of Dachau published by H. W. Gray in 1975 was probably his best-known among organists. He studied organ and composition at the Chicago Conservatory where his principal teacher was Leo Sowerby. He also studied with Claire Coci in New York.

Although not immediately identified with New York, Sifler held positions in churches and synagogues in Mt. Vernon, Kew Gardens, and Brooklyn before moving to California, where he held positions at St. Thomas Episcopal Church in Hollywood, and St. Barnabas Episcopal Church in Los Angeles.

The photo at right appeared in the March 1951 issue of The Diapason announcing his appointment as organist and director of the Canterbury Choir at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

Bronson Ragan

Kevin Walters, organist of Rye Presbyterian Church and Congregation Emanu-El also in Rye, and a former student of Ragan, wrote a memorial tribute which appeared in the April 1996 issue of The Diapason, from which the following is taken:

E. Bronson Ragan served the Church of the Holy Trinity on East 88th Street, the historic Rhinelander Church, from 1946-1971. He died suddenly at the age of 56, within a few months of completing twenty-five years as organist and choirmaster. A native of Rome, New York, Ragan graduated from the Institute of Musical Art (predecessor of The Juilliard School) with the artists’ diploma in piano and organ. His principal teachers were Gaston Dethier and David McK. Williams. In 1938 he was appointed to the theory faculties of both the Institute and Juilliard Graduate School, as it was then known. After service in the U. S. Army during World War II, he returned to New York and to the reorganized Juilliard School where he joined his longtime friend and colleague Vernon de Tar on the organ faculty. He remained until 1969 when he left Juilliard to become chairman of the new organ department of the Manhattan School of Music where he was already a member of the theory faculty. He also taught at Pius X School of Liturgical Music and The Guilmant Organ School from the early 1950s.

Of all his many professional activities apart from the Church of the Holy Trinity, Ragan would surely have said that the most important was his involvement in the examination program of the AGO to which he was passionately committed. He served several terms as a member of the examination committee and the national board of examiners, working to encourage thorough preparation on the part of candidates and to uphold uncompromisingly high standards on the part of examiners. All his students were expected to attend to the applied disciplines of transposition, harmonization, and score reading as diligently as to the learning of the organ repertoire. Where the latter was concerned, Ragan had a very definite preference: the music of J. S. Bach reigned supreme. Any organ music preceding Bach was derisively referred to as “pre-music” and, with the exception of Franck, he was largely unsympathetic toward much 19th and 20th century French music. Through his love of sixteenth-century counterpoint and vast knowledge of its diverse stylistic applications, he was able to communicate a considerable appreciation and understanding of this subject. His own playing was a model of rhythmic and technical precision and his improvisational abilities were phenomenal–he could extemporize a four-voice fugue on a given subject in virtually any style, but adamantly maintained that improvisational skills were largely “unteachable.”

In his last few years at Holy Trinity, the Skinner organ was diagnosed as “terminal and inoperable.” The church did not have adequate funds to repair or replace it, so Ragan reluctantly agreed to the purchase of a large electronic instrument. At about the same time, Holy Trinity found itself unable to maintain a fully professional choir. Rather than establishing a volunteer choir, Ragan proposed the rather startling idea (for that time) of calling upon his many colleagues and students to introduce instrumental music of all types into regular church services–everything from wind ensembles to a solo violoncello with all the repertory possibilities they brought with them. The result was more successful than had been imagined, and first-class instrumentalists were eager to play in the church with its excellent acoustics. His enthusiasm for this different approach to church music made many of us aware of new possibilities for repertoire and instrumental combinations with the organ.

Anne Versteeg McKittrick

Anne Versteeg McKittrick

Paul Richard Olson, organist of Grace Church, Brooklyn Heights, provided the following:

Anne Versteeg McKittrick, FAGO, FTCL, served as Organist and Choirmaster for 38 years at Grace Church, Brooklyn Heights, from 1939-1976. Mrs. McKittrick took full charge of the music program at Grace Church in 1939following the death of Frank Wright who had held the position for 43 years. She died on May 3, 1976 from complications of a heart attack. She played andconducted her last service on Easter Day, April 18, 1976. Her funeral service was held at Grace Church on May 6, 1976.

Anne McKittrick studied with Frank Wright, her predecessor, G. Darlington Richards, organist of St. James Church, NYC, and Norman Coke-Jephcott, organist of Cathedral of St. John the Divine. For many years she was very active in the work of the American Guild of Organists, serving on the Examinations Committee, the National Council, and as National Librarian-Historian. Mrs. McKittrick was known for her cheerful presence and her faithful service to the AGO.

Mrs. McKittrick’s work with the choir of men and boys brought great recognition and honor to Grace Church. She was married to Alfred Hadley Hanson, longtime member of the choir. He died in 1962. Mrs. McKittrick was succeeded by Bradley Hull.

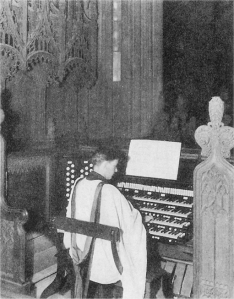

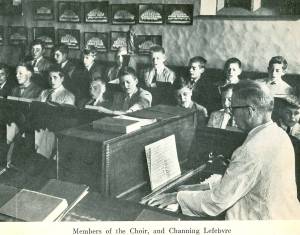

Channing Lefebvre (1894-1967)

Channing Lefebvre, scanned from the 1940 AGO National Convention booklet.

Channing Lefebvre is best remembered among organists as being the organist and choirmaster of Trinity Wall Street from 1922-1941 and Warden (the position was changed to President in 1949) of the American Guild of Organists from 1939-41.

But his name was held in even wider renown as director of the University Glee Club of New York from 1927-1961, and as music master and school organist of St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, from 1941-61.

Following his positions in New York and Concord, he lived in Manila, Philippines, for six years and was the organist of the Episcopal Church of St. Mary and St. John in Quezon City. In April 1967 he had just arrived in New York for a visit on his way to retirement in Digby, Nova Scotia, and attended a rehearsal of the University Glee Club for an upcoming concert in Philharmonic Hall, when he died the next day of chronic cardiovascular complications while staying at the Columbia Club.

He was a native of Richmond, Va. where his musical gifts were nurtured at an early age, particularly by his great uncle, the Rt. Rev. Channing Moore Williams, the Bishop of Japan, who was visiting his home church of St. Paul’s in that city. From that time on Bp. Williams supported his young namesake as he attended first St. Paul’s Choir School in Baltimore, and then Peabody Conservatory.

After early positions at St. Stephen’s Church in Washington, and assistant organist of at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, Lefebvre served during World War I in the Navy Reserve. Following that he served at St. Luke’s in Montclair, New Jersey, before being called to Trinity.

Before his long tenure with the University Glee Club, he founded the Down Town Glee Club, and served as director of the Musical Art Society of Orange, N. J., and of the Golden Hill Chorus, a group of women singers who worked in the financial district of Manhattan.

His obituary in The New York Times, dated April 22, 1967, states that he was 72 at the time of his death. It also says that “he was an inveterate pipe-smoker” and that “he used to conduct his chorus rehearsals without outbursts of temperament.”

He received an honorary doctorate from Columbia University sometime in the late 1930s at which time President Nicholas Murray Butler’s citation read in part that he was “born to love of music and early seeking a musical career; successively choirboy, organist, and now choirmaster and organist at Trinity, that ancient foundation to which this university is bound by ties that go back to its very birth.”

Rehearsing in the choir room at St. Paul’s School

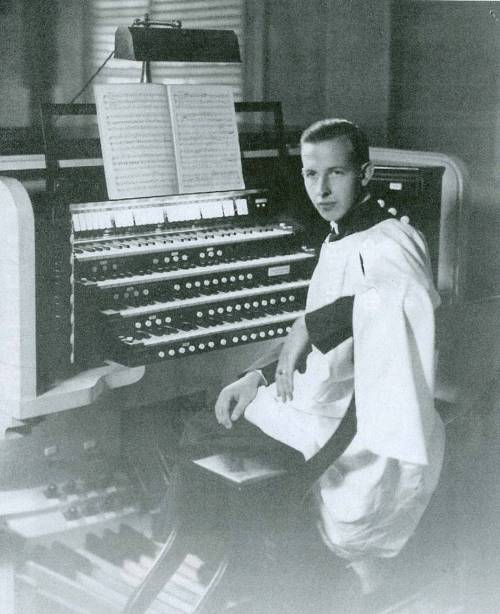

T. Frederick H. Candlyn (1892-1964)

Candlyn was born in Cheshire, England, and educated at the University of Durham. He emigrated to the United States in 1912 and held positions as Head of the Music Department at the New York State College for Teachers in Albany, and was the Organist and Choirmaster of St. Paul’s Church, also in Albany, for 28 years.

In 1943 he succeeded T. Tertius Noble at Saint Thomas Church, New York, where he remained until 1954, at which time he became Organist and Choirmaster of Trinity Church in Roslyn, Long Island.

He is the composer of much organ and choral music which remains in print.

George Markey (1925-1999)

Many members correctly identified George Markey, who graduated from the Curtis Institute of Music where his major teacher was Alexander McCurdy. He also studied with Leo Sowerby, Dimitri Mitropoulos, and Rudolf Serkin, and held an honorary doctorate from MacPhail College.

Markey taught at Westminster Choir College and the Peabody Conservatory, and was the director of the Guilmant Organ School in New York, where it was his unfulfilled dream for the school to compete with the major conservatories in organ studies. In New York he was also the director of music and organist of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church from 1961-70. He concertized throughout the United States, Europe, Australia, India, and Japan. He lived in Maplewood, N. J., and in his later years was the organist of the Episcopal Church of St. Andrew and Holy Communion in South Orange.

The photograph above was taken at the Wanamaker Organ in 1954.

Paul Callaway (1909-1995)

Paul Callaway, Mus.D., F.A.G.O. in the 1940 Washington, DC AGO National Convention booklet.

So associated was Callaway with music in Washington, D. C., that it is easy to forget that he began his career in New York. The son of a Disciples of Christ clergyman from Illinois, the young Callaway found his way to New York where from 1930-1935 he was an “articled pupil”—the term he always used—of T. Tertius Noble, and was the Organist and Choirmaster of St. Thomas Chapel, now All Saints Church on East 60th Street. It is generally acknowledged that, together with Andrew Tietjen and Grover Oberle, he was among Noble’s most talented and prominent pupils.

While at St. Thomas Chapel, where the Sunday evening services were at 8:00, he regularly turned pages at Evensong for David McK. Williams at St. Bartholomew’s and assimilated much of Williams’ style in his own service playing, especially in anthem and oratorio accompaniment. Although Callaway was careful to point out that he never studied formally with David McK. Williams, he was also quick to acknowledge Williams’ great influence upon him and his playing, and the two remained good friends until Williams died in 1978. Callaway was approached about succeeding Williams at St. Bartholomew’s in 1946 and he likely would have had he not just returned to Washington Cathedral from service in World War II, where he was a bandmaster in the South Pacific.

In a conversation with me Callaway said that one day Dr. Noble came to him unexpectedly and said “I want you to do some missionary work in Grand Rapids” and with that Callaway was packed off to his new post at St. Mark’s Church in that city in 1935. This was not entirely to young Callaway’s liking, who by this time had grown to enjoy New York, but he did as he was asked, and four years later Dr. Noble was instrumental in securing his appointment at the Cathedral in Washington where he was to remain for 38 years until his retirement in 1977.

Bach St. Matthew Passion at Peabody in the late 1950s.

He was a major force in the fledgling musical life of Washington. He founded the Cathedral Choral Society shortly after he arrived, and in 1956 he was the founding musical director of the Washington Opera Society, now known as the Washington National Opera. He also taught organ and directed the choir at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, and conducted opera in the summer at the Lake George Opera Festival in upstate New York. He was on the faculty of the College of Church Musicians, the extraordinary graduate school founded by Leo Sowerby for the training of organists and choirmasters (one of five schools on the cathedral close), which combined the rigors of conservatory study together with the master-apprentice approach afforded by its small size. During its short life the college had a tremendous influence on Episcopal church music throughout the country as its students gained appointments in large churches and cathedrals throughout the 1960s and 70s.

At the conclusion of a concert by the Cathedral Choral Society

In addition to his many other activities he was a virtuoso organist who maintained his technique and put his vast repertoire to use in cathedral services and the recitals which followed Evensong each Sunday. While he did not tour as a recitalist, he did frequently appear locally and within the region. In 1960 he was the soloist for the premiere of Samuel Barber’s Toccata Festiva which was written to inaugurate the new Aeolian-Skinner organ in Philadelphia’s Academy of Music and was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy.

At the console of the new Aeolian-Skinner organ in the Philadelphia Academy of Music, 1960

Callaway’s musical tastes were broad and catholic. Long before the early music movement gained anything like the prominence it holds today, he performed large doses of Renaissance and Elizabethan music with the cathedral choir, both settings of the ordinary, and anthems and motets, together with the standard English cathedral repertoire of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and copious amounts of contemporary music. In 1964 for the dedication of the Gloria in excelsis Tower, the central tower over the cathedral crossing, which is the only tower in the world housing both a carillon and a ten-bell ring, he commissioned music for carillon and a variety of instruments from Samuel Barber, Lee Hoiby, Stanley Hollingsworth, Roy Hamlin Johnson, John La Montaine, Milford Myhre, Ned Rorem, and Leo Sowerby.

With Ronald Rice, a student at the College of Church Musicians who became the first organist of the new Cathedral of St. Philip in Atlanta.

When he retired from Washington Cathedral he assumed the position of Director of Music at St. Paul’s K Street in Washington, the noted Anglo-Catholic parish, one of whose previous organists, Edgar Priest, was the first organist of the Cathedral. For his service to Anglo-American relations he was awarded the O.B.E. (which he said irreverently—referring to himself, we presume—stood for Old Bastard Extraordinaire).

He lived his life as hard as he worked: a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes was seldom far from reach, and when asked what drink he preferred, he said it was “gin before dinner, bourbon after.” I left Washington just before he went to St. Paul’s. When I saw him on a trip home shortly thereafter I asked him how he liked his new position, and he replied in his inimitable guttural growl “Oh yeah, I always wanted to play in one of those . . uh . . smoky places.”

His Requiem Mass, for which the Rt. Rev. James Winchester Montgomery was the celebrant, was held at the Church of the Ascension and St. Agnes in Washington, where he was a parishioner. Fr. Frederic Meisel was the preacher. Fr. Meisel was the long-time Rector of the church and a great friend of Callaway’s whom he met when he was Noble’s pupil, and young Freddie Meisel was a choirboy at St. Thomas.

Paul Callaway, 1977

Paul Smith Callaway is interred in the crypt columbarium of Washington National Cathedral, together with fellow musicians Leo Sowerby, Richard Dirksen, J. Reilly Lewis, and Edgar Priest, cathedral architect Philip Hubert Frohman, and various bishops and clergy associated with the Cathedral.

Virgil Fox (1912-1980)

Virgil Fox in 1932

When I added Fox to the Members from the Past column I tried to find the oldest picture of him I could find in the hope of lessening the obviousness of his identity. Clearly I failed in that attempt since more members correctly identified Fox than any previous entry.

So much has been written about Fox that a detailed sketch here seems superfluous. Thirty years after his death his legacy is still widely known and discussed passionately, often with the most conviction by those born since he died!

Virgil Fox was the organist of The Riverside Church from 1946-1965, sharing his tenure with his partner Richard Weagly, who was the choir director. As they had in their previous position in Baltimore at Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, Fox and Weagley set a new standard for music at Riverside, and in New York.

Virgil Fox with Richard Weagly shortly after their appointment to Riverside.

While in Baltimore, Fox also taught organ at the Peabody Conservatory where among his pupils were Richard Wayne Dirksen, William Watkins, Milton Hodgson, Marie Schumacher, and Helen Howell Williams.

For the Sixtieth Anniversary AGO National Convention held in New York in 1956, Fox served with Robert Baker as co-chairman of the convention, which was attended by the largest number in the Guild’s history at the time. He also was a member of the AGO national council and was one of the organists chosen to open the new organ in Philharmonic Hall, as Avery Fisher Hall was known when it was new.

Virgil Fox at the organ in his home in Englewood, New Jersey, in the late 1970s.

Walter Baker (1910-1988) was widely regarded as one of the leading concerts organists of his generation. He graduated from the Curtis Institute of Music in 1938 where he was among the first pupils of Alexander McCurdy. Prior to that he spent some time in California as a semi-professional boxer.

While still a student at Curtis, he became the organist and choir director of the First Baptist Church in Philadelphia, founded the Oratorio Society of Philadelphia, and was added to the roster of organists who toured under the management of Bernard LaBerge.

In 1948 he left First Baptist Church and increasingly became involved in conducting in Philadelphia and New York. He was from 1948-51 assistant to Dimitri Mitropoulos for concerts by the New York Philharmonic. He also worked closely with the music department of the Wanamaker store in Philadelphia, which at that time often featured concerts with full orchestra and organ. On Good Friday 1948 he conducted what is believed to be the first televised performance of Wagner’s Parsifal with the Philadelphia Orchestra and a chorus of 300 in the Wanamaker Grand Court.

From 1949-59 he was the organist of the Lutheran Church of the Holy Trinity in New York and taught, at various time, at Westminster Choir College, Peabody Conservatory, and the Mannes College of Music. The last years of his life were plagued with ill health and a series of strokes curtailed his activities, although he continued to play on occasion.

Alec Wyton (1921-2007)

The photograph at right appeared in the December 1950 issue of The Diapason announcing Wyton’s appointment to Christ Church Cathedral in St. Louis.

Alexander Francis Wyton, his given name, was born in London on August 3, 1921. He was a choirboy at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Northampton and his first teacher was Ralph Richardson Jones. At age twelve, after his voice changed, he held his first church position as organist of a village church. After graduating from high school he held apprentice jobs in chemistry and law before joining the Royal Signal Corps. During his military service he prepared for his F.R.C.O. examinations which he passed at age nineteen. Formal organ study included work at the Royal Academy of Music where he studied with the legendary virtuoso G. D. Cunningham. He received his B.A. from Exeter College of Oxford University in 1945. While at Oxford he was organ scholar and sub-organist of Christ Church Cathedral working under Sir Thomas Armstrong.

In 1946 Wyton was appointed organist and choirmaster of St. Matthew’s Church in Northampton where the Vicar, the Rev. Walter Hussey, had inaugurated a program of commissioning works to celebrate the parish’s patronal feast each year. Two years before Wyton arrived Britten wrote Rejoice in the Lamb for that occasion, and it was during Wyton’s first year in Northampton that Britten that wrote his only organ work, Prelude and Fugue on a Theme of Vittoria, for him.

In 1950 Alec Wyton was invited by the Bishop of Dallas to come to Texas and create a boy choir. He accomplished this in six months at what is now St. Mark’s School in Dallas. In September of that year he became the Organist and Choirmaster of Christ Church Cathedral in St. Louis, a position he held until he came to New York in 1954 to be the Organist and Master of the Choristers and (later) Headmaster of the choir school at the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine.

Taking a daily rehearsal at the Cathedral Choir School.

His work flourished in his early years at the cathedral, as he maintained a rigorous schedule of daily rehearsals and services in the English cathedral tradition of his predecessors Miles Farrow and Norman Coke-Jephcott. He relinquished his duties as Headmaster in 1962. As the liturgical innovations of the 1960s gained momentum, Wyton responded in kind, furnishing the cathedral with a wide range of musical expression, commissioning works from Duke Ellington, Ned Rorem, and Benjamin Britten, as well as offering his own compositions for use in the trial liturgies which emerged prior to the new Book of Common Prayer. He also was responsible for bringing personalities such as Leopold Stokowski and the cast of “Hair” to the cathedral.

With Leopold Stokowski at the Cathedral.

He was the president of the American Guild of Organists from 1964-1969 and was twice dean of the NYC Chapter. He also taught at various times at Union Theological Seminary, Westminster Choir College, and Manhattan School of Music.

He left St. John the Divine in 1974 to take the position at St. James’ Church on Madison Avenue, where he remained eleven years. The story has been widely told of St. James’ Rector calling Wyton asking for a recommendation to fill the vacant position and Wyton replied somethng to the effect of “would you consider an aging cathedral organist?” During his time at St. James he was the coordinator for the Episcopal Church’s Standing Committee on Church Music which produced the Hymnal 1982, the hymnal still used in the Episcopal Church.

At the console of the Cathedral Organ, Aeolian-Skinner Opus 150-A.

In 1985 he moved to Ridgefield, Conn., to become the Minister of Music at St. Stephen’s Church, a church he had known since his early cathedral days when he would take choirboys annually for a day in the country at the nearby estate of a cathedral patron, which always concluded with Evensong at St. Stephen’s.

Wyton was a prolific composer of music for choir and organ, some of which is still in print. For the legendary 1956 national convention of the AGO he wrote Fanfare for the State Trumpet which was premiered by Charlotte Garden at St. John the Divine. It was later published by H. W. Gray titled simply Fanfare and is dedicated “to G. Donald Harrison who created the State Trumpet.” Harrison was known to have said that it was the only piece of music ever dedicated to him.

Alec’s funeral was held on Friday, March 23, 2007 at St. Stephen’s Church in Ridgefield, Conn., and his ashes are interred in the columbarium of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine.

Lillian Clark appears in photo at right which was in the December 1952 issue of The Diapason announcing her appointment as the assistant organist of St. Bartholomew’s Church. The announcement told that in addition to assisting the then organist, Harold Friedell, Miss Clark was to be in charge of the junior choir. She held the AAGO certificate and was a member of the AGO National Council.

appears in photo at right which was in the December 1952 issue of The Diapason announcing her appointment as the assistant organist of St. Bartholomew’s Church. The announcement told that in addition to assisting the then organist, Harold Friedell, Miss Clark was to be in charge of the junior choir. She held the AAGO certificate and was a member of the AGO National Council.

Attempts to find definitive dates for Miss Clark were inconclusive. Fred Swann responded saying that she was Friedell’s assistant before he was, and that he presumed that she was no longer with us, but I have not been able to confirm that. At any rate, she was one of several female organists in prominent positions in and around New York in the middle of the last century.

She began her piano studies in metropolitan New Jersey, and first studied organ with Frank Scherer at St. Luke’s Church in Montclair. Before going to St. Bartholomew’s she held several church positions in New Jersey and played recitals frequently, including appearances at the Portland (Maine) City Hall and the John Hays Hammond home (now museum) in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Harold Vincent Milligan (1888-1951)  is pictured at the console of the original Hook & Hastings organ in The Riverside Church. The photograph is by the noted photographer Margaret Bourke-White, and is one of several of her photographs which appeared in the December 20, 1937 issue of Life magazine with an article about The Riverside Church.

is pictured at the console of the original Hook & Hastings organ in The Riverside Church. The photograph is by the noted photographer Margaret Bourke-White, and is one of several of her photographs which appeared in the December 20, 1937 issue of Life magazine with an article about The Riverside Church.

Milligan was an organist, composer, writer, and arranger. He spent his early life in the Pacific Northwest and was from an early age the organist in churches where his father was the minister. He came to New York in 1907 to study with William C. Carl at the Guilmant Organ School. In addition to Carl, he also studied with T. Tertius Noble, Clement R. Gale, and Arthur E. Johnstone.

After one year as organist of the First Presbyterian Church in Orange, New Jersey, he worked for five years at Rutgers Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, and two years at Plymouth Church in Brooklyn. In 1915 he was appointed organist at the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church, remaining with the church throughout the era when it moved several times, culminating in the building of a new church in Morningside Heights renamed The Riverside Church. He held this position until 1940.

From 1929-1932 he served as the president of the National Association of Organists, which later was folded into the American Guild of Organists, and was the secretary of the AGO from 1926-1951. For many years Milligan wrote articles and reviews for The Diapason and The New Music Review, and was a columnist for The American Organist and Woman’s Home Companion. He was the author of Stories of Famous Operas (1950), and edited The Best Known Hymns and Prayers of the American People (1942), and (with Geraldine Soubaine) The Opera Quiz Book (1948). He also authored short fiction, lectured on opera at Columbia University, and was associate director of the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts.

Milligan composed two operettas for children,The Outlaws of Etiquette (1913) and The Laughabet (1918), and incidental music for several plays, as well as numerous songs, sacred and secular choral works, and organ music. He is probably best remembered by the general public as the collector and editor of four volumes of previously undiscovered 18th century American songs, chiefly by Francis Hopkinson, a leading musician in colonial America and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Milligan also wrote the first biography of American songwriter Stephen Foster in 1920.

His papers are held by the music division of the New York Public Library, the web site for which also provided most of the information contained in this biographical sketch.

Gottfried Federlein (1883-1952)

Gottfried Federlein (1883-1952)

Federlein is best remembered as the organist of Temple Emanu-El from 1915-1945, first at the former temple at Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street, playing the J. H. & C. S. Odell organ, and then at the present location at Fifth Avenue and 65th Street when the congregation merged with Temple Beth-El, where he played the large new Casavant organ.

Federlein also served several churches in the metropolitan area including Marcy Avenue Baptist Church in Brooklyn, the Church of the Incarnation, Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Trinity Church and the Society for Ethical Culture in New York, and Central Presbyterian Church in Montclair, New Jersey.

He studied at Trinity School and the Institute of Musical Art where his teachers included Edward Biedermann, Percy Goetschius, and Louis V. Saar. He was the composer of many works in various genres for the church, synagogue, and concert hall, and was a member of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers. He earned the FAGO in 1904 and served the Guild in several capacities, including sub warden, as the position of vice president was then known. In 1915 he received the AGO’s Clemson Prize for best anthem for mixed voices and organ.

William Whitehead (1938-2000)

Whitehead was the Director of Music and Organist of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church from 1973-1990. Prior to that he served at First Presbyterian Church in Bethlehem, Pa., where he was also organist of the Bach Choir of Bethlehem.

He attended Baylor University and was a graduate of the University of Oklahoma, the Curtis Institute of Music, and Columbia University. In 1962 he was the first organist to win the annual Young Artist Award of the Philadelphia Orchestra, which included a performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra under the direction of Eugene Ormandy.

At various times he was on the faculty of the Guilmant Organ School, Mannes College of Music, and Westminster Choir College, and he toured under the auspices of the Lillian Murtagh management, now Karen McFarlane Artists. He was formerly the dean of the Lehigh Valley chapter of the AGO, and was later elected to the Guild’s national council. He was also a founder of the Presbyterian Association of Musicians.

After leaving New York he served at Kirk in the Hills Presbyterian Church in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, and at the time of his death he was Minister of Music at Second Congregational Church in Greenwich, having served as guest organist at several Connecticut churches since 1995.

J. Warren Andrews (1860-1932)

The photo is from Andrews’ obituary which appeared in the December 1942 issue of The Diapason which noted that he died January 18 of that year. Andrews was one of the founders of the American Guild of Organists and at the time of his death had been the organist of the Church of the Divine Paternity (now Fourth Universalist Society) for 33 years. He was on the national council of the Guild for over 25 years and the first AGO national convention was held during his term as warden, as the office of president was then called.

Born in Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1860, he studied with Charles H. Wood and Eugene Thayer. After student positions in Massachusetts, he became the organist and choirmaster of Trinity Church in Newport, Rhode Island, at age 19, directing its boychoir. Following that he served at Pilgrim Church in Cambridge, Mass., and Plymouth Church in Minneapolis, before moving to New York.

Andrews was also elected president of the New York State Music Teachers Association in 1908. Following funeral services at the Church of the Divine Paternity, there were Masonic ceremonies conducted by members of the Roome Lodge, and he was buried in Pine Grove Cemetery in Lynn, Mass.

Robert Owen (1918-2005)

Robert Owen at the new Aeolian-Skinner organ in Christ Church, Bronxville, 1949.