This monograph was originally published as two separate articles in the March and April 2021 issues of the Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians to observe the 100th anniversary of Dirksen’s birth. It also appeared in condensed form in the January 2022 issue of The American Organist, and was the basis for two separate webcasts sponsored by Washington National Cathedral and the American Guild of Organists to observe the centennial of Dirksen’s birth. Taking advantage of post-production interviews and feedback, what follows is an expanded and edited compilation from all available sources.

Part I—Biography

Introduction

When considering the attributes of Richard Dirksen’s career, “multi-talented” is the term most often used. That is accurate, but incomplete. He could easily have pursued a successful career as a concert organist, conductor, composer, producer, educator, impresario, administrator, organbuilder, church musician . . . or a clergyman. In truth, he was a 20th century Renaissance Man, though that too is a well-worn cliché. In the final analysis his career was a synthesis of each of these disciplines practiced at a high level of achievement at Washington National Cathedral, where he was to spend his entire career.

When Dirksen was appointed in 1942 the physical edifice of the cathedral was but a nascent vision of what it was to become, but it was still a highly visible presence in the city of Washington, throughout the Episcopal Church, and the Anglican Communion—and Dirksen grew as the cathedral grew.

Known professionally as Richard Dirksen—that is how he was listed as composer, performer, or conductor—but to family, friends, and throughout the cathedral community, Dirksen was always known as Wayne. Even in his student recitals he was listed as Wayne Dirksen, or R. Wayne Dirksen.

The cathedral’s formal ecclesiastical name is the Cathedral Church of Saints Peter and Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington. At the time of Wayne’s appointment in 1942, and through most of the 20th Century, it was known as Washington Cathedral in all of its in-house publications, orders of service, and press articles. This followed typical English custom where the various cathedrals (excepting St. Paul’s) are identified by their location, though they each use their full ecclesiastical names on formal occasions. The “national” part of the appellation was usually given by others, suggested no doubt by the fact that George Washington and Pierre L’Enfant, in their plans for the new Federal city, called for the building of a great church for national purposes. Considering the era that the bulk of this article addresses, I’ve opted to use Washington Cathedral, or simply “the cathedral.”

The year before his death Wayne gave some remarks at a Regional AAM gathering which summarized his thoughts about the singular importance the cathedral had on him:

Now a comment on the strongest influence on my life and work: the vast dimension of the cathedral itself must be noted. Its magnitude and beauty offer endless inspiration to the artist and ennoble the richness of its worship and culture. An incomparable esthetic paragon, it is unlimited in challenge for special gifts and service, ever inviting discerning attention and attracting excellence. Its essence is that of the Eternal and Mysterious Holy One, accessible to human aspiration. Therein lies its greatest power.[1]

Early Life

Richard Wayne Dirksen was born on February 8, 1921 in Freeport, Illinois, northwest of Chicago, into a Presbyterian family that organized its life around music, organs, and church. His father was an organbuilder and his mother an organist. The family was distantly related to the famous senator from Illinois, Everett Dirksen, though from a different branch of the family. Wayne’s visage evoked a resemblance that was striking enough that the question is often asked.

Wayne’s father, Richard Watson Dirksen, was the only child of Freeport’s major contractor who displayed facility in the manual arts at an early age and by adolescence was thoroughly familiar with the equipment of the building trades. A project at the local theatre included overseeing the installation of an organ and the elder Dirksen’s fascination with it sealed the path his life’s work. He founded the Freeport Organ Company and was later associated with Reuter.

Organ building requires a comprehensive knowledge of every building technique: electricity, metalwork, air conduiting, fine- and large-scale mechanics, cabinetry, acoustics, not to mention sales. As his son, Wayne was surrounded with these skills and that knowledge served him well. On his first morning in Baltimore to attend Peabody Conservatory . . . he heard a stuck note while passing a church, went in, introduced himself, fixed it, and made his first friend in town.[2]

As a boy, young Wayne was recruited to sing in the boychoir of Grace Episcopal Church in Freeport and, in a scenario to which many can relate, his family soon joined him as active members of the parish, although his mother continued as the organist of another church. He graduated from Freeport High School in 1938, where he was a member of the National Honor Society, a drum major, played the bassoon in the band, and won first place in the National Music School Competition. He studied piano and organ with his mother and others locally, but planned to pursue a career in the ministry and, with the help of his rector, was awarded a scholarship to Hobart College for that purpose.

However, he was drawn to music and, in what must have been a bold decision, declined the scholarship and spent the year following graduation seriously studying organ, piano, and theory with Hugh Price(one of Virgil Fox’s teachers) preparing for auditions to a conservatory. After a failed attempt to gain a spot at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, he was awarded a scholarship at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore in 1940 where he was a student of Virgil Fox, who was twelve years older than Wayne and was already in demand as a concert organist.

Peabody and the Appointment to Washington Cathedral

Wayne’s student notebook from Peabody is a fascinating snapshot into Virgil Fox’s teaching methods, and is worthy of serious study at another time. Fox went into extreme detail about matters of technique, including fingering and pedaling indications which he insisted his students use. Fox was not the sort to encourage a lot of individuality. He insisted on doing it his way.

Fox’s syllabi and class handouts indicate that he had given much thought and preparation, and was very methodical. Everything was worked out in advance and little was left to chance. Assignments in technique, repertoire, registration, and style were specific, and lessons were arranged to accommodate Fox’s increasingly demanding concert schedule. Wayne regularly played at conservatory exhibitions, concerts, convocations, and accompanied choral ensembles. His growing repertoire was eclectic, with a heavy concentration of the works of Bach . . . and his recitals were played from memory.

During the first two years at Peabody, Wayne was the organist of the First Methodist Church at St. Paul and 22nd Streets, the “Mother Church of American Methodism” as the church was known then and now. The church traces its history to 1774 as Lovely Lane Meeting House, and it was at a conference there in 1784 that the denomination known as the Methodist Episcopal Church was formed. In 1884 the church (by then known as the First Methodist Episcopal Church) moved into an impressive new church designed by Stanford White in the Romanesque Revival which was built as the “Centennial Monument of American Methodism.” An active congregation still occupies the landmark building, though the congregation reverted to its original name and it is now known as the Lovely Lane United Methodist Church. At Sunday morning and evening services the organ and choir, under the direction of Edward H. Stewart, offered a comprehensive repertoire typical of the era.

In January 1942 Paul Callaway (1909-1995), the organist and choirmaster of Washington Cathedral, came to Peabody to audition students to be his assistant. Callaway had been at the cathedral since 1939 and was just getting started on ambitious plans which necessitated acquiring an assistant. At this time Callaway would have been in his early 30s, slightly more than a decade older than Wayne.

Also interviewed for the position were Milton Hodgson and William Watkins, who were also students of Fox at Peabody. Hodgson remained in Baltimore for the remainder of his life and was the music director of WMAR Radio-TV for 30 years. He died in 1981. After graduating from Peabody, Watkins had a very successful early career as a concert organist which was curtailed by a serious automobile accident that left him impaired. He was a much-beloved teacher and church musician in Washington until his death in 2004.

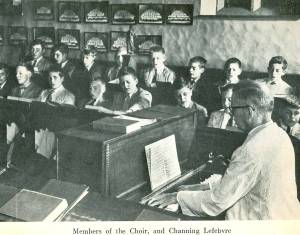

Wayne began his duties at the cathedral in the early spring of 1943, just in time for Lent, Holy Week, and Easter preparations. His basic duties were to train the Junior Choir, a rather large training choir from which were selected boys for the main cathedral choir. This choir sang under Wayne’s direction weekly at early Sunday services in Bethlehem Chapel. Although he shared some of the playing of voluntaries with Callaway, the now-familiar custom of the assistant organist doing the bulk of the accompanying while the boss directed the choir was not in vogue. Callaway did almost all of the choral direction while accompanying from the console, and the assistant’s typical task was to turn pages.

Wayne commuted from Baltimore the rest of the semester until he graduated in May. Most of the graduating class received certificates or diplomas indicating successful completion of a three-year prescribed course of study; only three actual degrees were conferred—one M.Mus, and two B.Mus. Most students graduated with a Teacher’s Certificate. Wayne received the Church Organist’s Certificate, the only one that year.

Early indications show that Wayne’s relationship with his new boss was complementary and harmonious. Writing to his family back home in Illinois he says, speaking of Callaway:

He is very energetic and a titan of a musician, handling his choir with an iron hand. He is not the organist Virgil is, but that is not to be expected . . . there is much I am learning from him, especially about service playing. He is unmarried, smokes a lot, drinks a little (better delete the latter for dear Grandmother), drives carefully, is a swell fellow, and has been grand to me.[3]

Wayne’s opinion of Callaway’s playing must have strengthened in the ensuing weeks as he wrote to his family about a month later, describing a recital Callaway had played the previous week:

He is every bit the organist that Virgil is, with as much technique, the only difference being that he doesn’t play from memory.[4]

And Wayne’s description of his first Easter Day is memorable:

Then came the 11:00 service, and about that I can hardly say a thing, for it was something I shall never forget. The processional—with flags, banners, nine clergymen, the Dean—all of it like I have always dreamed Easter Sunday would be—was, in fact, somewhere. I had nothing to do but sit back in the alcove behind the organ console and enjoy it, and the emotions with which I was filled that morning were of every description—dominated by pure joy. The music was perfection itself, and the brass and tympani augmenting the organ raised the vaulted arches right off the pillars.[5]

Since he had a low draft number Wayne decided to enlist, rather than wait to be drafted. In fact, he enlisted the very day after his graduation recital at Peabody. Paul Callaway also left the cathedral for army duty as a warrant officer and bandmaster in the Pacific.

Filling in for them at the cathedral for the duration of the war was Ellis C. Varley, a name largely forgotten now. Varley went on to a distinguished career at the Cathedral Church of St. Paul in Detroit. He previously held positions in Ohio at St. Paul’s in Akron and Grace Church in Sandusky. He was also the personal organist to the Firestone family and his performances were regularly broadcast over the Cleveland radio stations. At the time of his death in 1954 at age 63, he had been organist of St. John’s Cathedral in Jacksonville, Florida, for less than a year.

Army Life During World War II

After enlisting in the Army, Wayne was assigned to be a chaplain’s assistant at Walter Reed Army General Hospital where he was the organist and sexton for the hospital chapel. The chapel on the campus is an attractive edifice in the English Gothic style which contained a nice three-manual Skinner organ. It was a popular site for weddings, sometimes as many as eight per week, for which Wayne received fees over and above his military pay, most of which he was able to save according to letters home to his family. He also had a few pupils and played for a Jewish synagogue—all of which was a prelude to the pattern of work he was to maintain for the rest of his life. He always had several jobs.

Of particular interest, one of his duties at Walter Reed was program director and announcer for the hospital radio station WRGH. The original station consisted of individual headphone jacks by each bed. It had been the gift of New York theatrical producer Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel and was inoperative by the time Wayne arrived, though most of the hardware was still in place. Wayne and his team gained permission and a modest budget to rebuild the system and they began to gather replacements parts from any source they could find, such as a pinball repair shop in downtown Washington. In short order they rebuilt the campus radio station complete with a soundproof studio, master control board, a library of LP recordings, and two outside channels from which to choose. In this capacity he introduced several innovative features and programs. The station’s work was even featured in an article in the New York Times Magazine written by well-known columnist Meyer Berger.[6]

A lively family recollection gives an interesting snapshot into the politics and logistics on the hospital campus:

1944 was an election year, Roosevelt running for his fourth term against Thomas Dewey. Then, as now, candidates were to receive equal amounts of media time, but Roosevelt refused to campaign as the war was in full cry. Speeches by either candidate were therefore hard to come by, but on Monday, October 5, at 10 p.m. Dewey was scheduled to give one on CBS. Unfortunately there was to be a prize fight at the same time on NBC. The majority of the officers, being Republicans, wanted to hear Dewey’s speech; the enlisted men, being soldiers, wanted to hear the fight.

Now bearing in mind that WRGH had only two channels available, and that after 5 p.m. the master control switch in the studio determined what single channel was heard throughout the hospital, the station operatives had a decision to make. They opted (privately) for the fight. So at 10 p.m. that night it was necessary that the person on duty (Cpl. Bradley) turn the switch from CBS to the fight on NBC. For whatever reason, he missed it. Now that would have been fine: the officers would happily have listened to Dewey, and the enlisted men, grumbling, would have gone to sleep. But upon discovering the mistake, some five minutes into the speech, he did switch to the fight, thus cutting off a presidential candidate’s rhetoric in mid-flight.

The repercussions were swift. Dad was enjoying a quiet evening at home when the call came at 10:15 to report to the base IMMEDIATELY, and we can surmise that the next few hours were singularly unpleasant. It was also no surprise that his orders to report to infantry basic training at Fort Barkley, Texas, came three days later. Wayne says now that the war was escalating so fast that he would have been called up sooner or later anyway, but this incident, which had received media attention by this time, was doubtless no hinderance to that.[7]

Wayne spent the remainder of World War II serving in the infantry until he mustered out in November 1945 with a rank of sergeant. The war in Europe ended as he was en route to Germany, so he spent his remaining months in uniform with a traveling six-man show he created for troop entertainment traveling throughout northern Europe.

On January 9, 1943 in Freeport, Illinois, Wayne married his high school sweetheart, Joan Shaw, the daughter of Elwyn Riley Shaw, a justice of the Illinois Supreme Court, and later a federal judge on the U. S. District Court for Northern Illinois, appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt. President Roosevelt also appointed Judge Shaw to the National Railway Labor Panel in 1943, and in that capacity the Shaws were frequent visitors to Washington during the Dirksens’ early married years. There is every indication that the two families were closely linked.

Second Call to Washington Cathedral

At this point Wayne had in mind moving to New York to pursue a career as a musician and composer in the theatrical milieu of Broadway. His assistantship at Washington Cathedral was basically a convenient part-time job while he finished at Peabody and the thought of a career there was not on his radar screen at all.

Ellis Varley received the call to Detroit, and all persons who left their jobs to serve in the war were entitled to return to their old positions when the war was over. So it was that Wayne was invited back to the cathedral and when Callaway returned in March 1946 they were reunited at the cathedral for a second time. Thus began a working relationship that lasted until Callaway retired in 1977.

Much could be written about the association of these two musical titans. As if to exemplify their obvious difference in size and height, they were just as different in temperament, personality, and in their approach to music. Yet, they were also entirely complementary and compatible. Callaway, who never married, was a frequent guest in the Dirksen home and he was the godfather to the Dirksen’s second child, Geoffrey Paul Dirksen.

It was about this time that Dirksen’s career as a composer began to evolve with ever more seriousness and his compositions began to appear regularly on cathedral music lists. One of the hallmarks of Callaway’s lengthy tenure was his eagerness to infuse a distinct American component into the historically Anglican cathedral style.

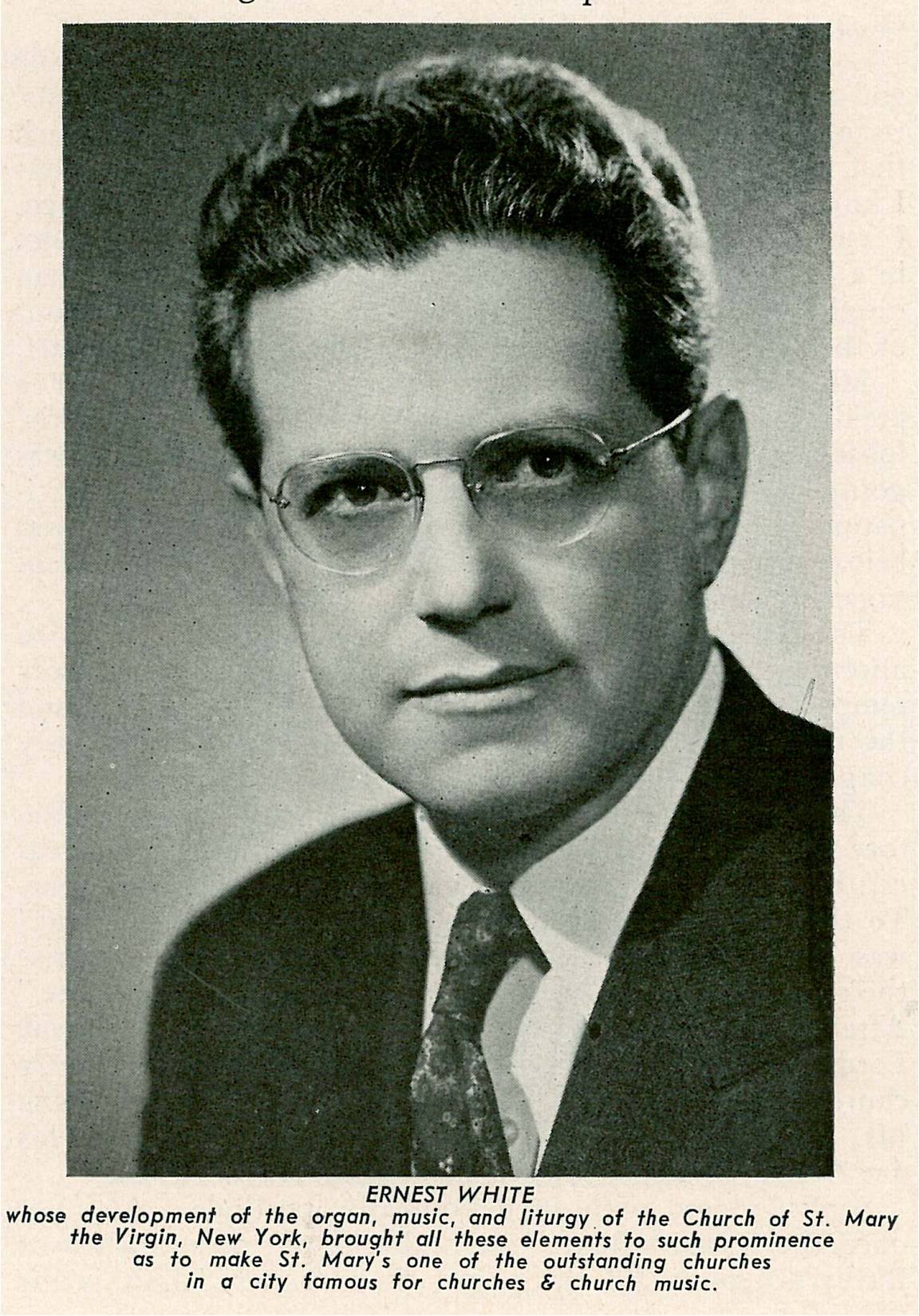

It’s a curious attribute given that T. Tertius Noble, the quintessential Englishman, was Callaway’s great mentor—an “articled pupil” was the term Callaway used, to denote the master-apprentice relationship they shared. I believe that it was the strong influence of David McK. Williams and his very eclectic musical program at St. Bartholomew’s Church in New York that set that pattern in motion. Callaway was careful to say that he was not technically a student of David McK. Williams, but he admitted to me that he learned a lot from him and had turned pages for him weekly at Sunday Evensong, and observed at close range a lot of his unique style and repertoire.

So it is not a surprise that Callaway would have taken increasing notice of his young assistant’s growing oeuvre and basically performed whatever Dirksen wrote. In return, the cathedral obtained in Wayne the services of a de facto composer-in-residence for the rest of his life.

For the 150th anniversary of the District of Columbia Paul Green produced an outdoor drama titled “Faith of Our Fathers” which inaugurated the new Carter Baron Amphitheater in Rock Creek Park and attracted wide attention. Green had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1927 for his drama “In Abraham’s Bosom” and had written several large-scale outdoor productions, the best-known of which was “The Lost Colony” about the disappearance of the Indian colony on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, which is still produced in the summer. For “Faith of Our Fathers” Dirksen was commissioned to write the music and conduct performances by musicians of the National Symphony Orchestra. The production ran for two years in the summer. This highly visible format gives an idea of Dirksen’s growing renown apart from the cathedral.

Wayne was but 29 years old at this time and it is remarkable that he would have been tasked with so highly visible a commission—not just the composition of the music, but he was charged with auditioning and assembling the musicians (mainly from the National Symphony Orchestra), rehearsing them, and conducting the production over the show’s two-year run.

It has been suggested that this meteoric rise came about through a thin line of association involving Paul Hume. Remembered by the general public primarily as the music critic of The Washington Post from 1946-1982 who wrote a critical review of a solo recital by Margaret Truman, daughter of the president, in December 1950 in which he said:

Miss Truman is a unique American phenomenon with a pleasant voice of little size and fair quality—(she) cannot sing very well—is flat a good deal of the time—more last night than at any time we have heard her in past years—has not improved in the years we have heard her—(and) still cannot sing with anything approaching professional finish.

President Truman penned a famous rebuttal to Hume saying, among other things, that:

Some day I hope to meet you. When that happens you’ll need a new nose, a lot of beef steak for black eyes, and perhaps a supporter below![8]

But few people remember that Paul Hume was also a professional singer who sang in such things as early performances of Menotti operas . . . and he was the baritone soloist in the choir of Washington Cathedral at just about the time Wayne came on the scene. One theory is that Hume heard some of Wayne’s youthful compositions, including his epic 1948 Easter Anthem Christ Our Passover, and recommended him to Paul Green.[9]

Assistant-itis

By 1950, Dirksen admitted to getting “assistant-itis.” Working for Callaway “involved a lot of page-turning,” he said; and he felt that he was just “hanging around” too much. He asked Bishop Angus Dun if he could start a mixed-voice glee club from students at the National Cathedral School [for Girls] and St. Albans [School for Boys].[10] Dirksen commented, “In those days the kids never even dated one another. Certainly to this point, the two schools never shared classes.”[11]

This began a pattern of creative collaboration between clergy, musicians, and the two schools that would continue and strengthen throughout Wayne’s career at the cathedral. This was facilitated by a turnover in the leadership at the two schools on the close, and a new cathedral dean. Even though the cathedral was (is) the bishop’s church, Bishop Dun, and his successor Bishop William Creighton, delegated total control of the cathedral’s worship life and operation to the new dean, the Very Rev. Francis B. Sayre, who charted a path that ultimately led to the completion of the building of the cathedral. At the same time, his vision also demanded that the cathedral assume an ever-expanding, ever-visible role in the religious, artistic, and civic life of cathedral community, the city, and nation. All of the musical forces of the cathedral community were included in this mandate, including the inception of the College of Church Musicians.

By combining the upper school glee clubs of the two school on the cathedral close, it was possible for the first time have a full SATB chorus in the curriculum. St. Albans and NCS were each 4th-12th grade, which guaranteed a full complement of tenors and basses, and the girls provided a high level of vocal maturity. Wayne immediately challenged the group to the point where they attained semi-professional status. The repertoire was comparable to that of a fully developed community chorus and concerts were presented to professional standards which often received favorable reviews in the press. In Wayne’s own words:

Whatever the Glee Clubs sing is apt to be hard and fiercely dealt with because we have little time to rehearse. So, a 13-year-old boy comes to his first rehearsal and you shove in his hands the Haydn Seasons, 212 pages thick, eight-part chorus, and maybe he has never seen a bar of music before. And you say to him, “Oh, by the way, we’re singing in German. OK? Here we go!

Of course the first two or three weeks some of them are pretty well snowed. So I say “be very quiet and listen. Before music can come out of the mouth it has to go in the ear and be in the brain,” and soon they can sing.[12]

The combined glee clubs also began to participate in cathedral liturgies, school chapel services in the cathedral, even substituting for the cathedral choir on occasion. Especially appealing to Wayne’s interest in musical theater, was the opportunity to compose operettas—usually with his wife, Joan, as librettist—which were regularly produced as part of the school’s program.

In addition to these new duties at the schools, Wayne continued his duties assisting Callaway, though by now he was given the title of Associate Organist and Choirmaster. This he did in addition to an increasing presence on the Washington musical scene. He taught organ at American University, directed the Department of Agriculture Chorus and the Doctor’s Symphony, an affiliate organization of the National Institute of Health, and was the director of the B & O Chorus in Baltimore. He made frequent appearances as a collaborative keyboard artist throughout the region, and he was especially known as an extraordinary continuo player improvising from figured bass notation. He also made occasional appearances playing organ in large-scale works for chorus and organ. He played the organ in the pit orchestra for the world premiere of Leonard Bernstein’s Mass which had been commissioned for the inaugural of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1971.

Beginning in the early 1950s services and events at the cathedral began to be televised. By the 1960s it was standard programming for the Christmas Day services from the cathedral to be broadcast nationally on network television. Wayne increasingly found himself directing the technical and logistical details of these, including notated scripts timed to the minute which the participants and choir followed. In addition to all of this, he continued to compose for these and many other diocesan events inherent in the life of the cathedral church of the diocese.

Tower Dedication in 1964 and New Duties

A significant building decision with lasting implications faced the cathedral as the new decade appeared on the horizon: build the tower, or complete the nave interior? There were persuasive arguments on each side, but it was decided to build the tower. Included in the tower plan was the installation of a ring of ten bells for change ringing, and a 54-bell carillon—the only such tower in the world to contain each.

The tower was dedicated on Ascension Day 1964 in a marathon day of services, concerts, and dramatic presentations; documentary videos on bells and change ringing played on a loop during open houses at the schools. The services and closing concert, accompanied by various instrumental ensembles featuring the carillon were held outdoors, and an altar was set up at the top of the Pilgrim Steps leading downward from the south transept. All of the musical organizations on the close were involved. The day began at 7:00 a.m. with fully choral services of Holy Communion, Morning Prayer at 10:15, various dedications and playing of the new carillon and changes on the ten-bell ring, Evensong at 4:00, and concluded with an evening concert with full orchestra, cathedral choral society, and glee clubs of the two schools, all gathered at the base of the dramatically lit new south transept and tower, now the highest point in the city.

The cathedral had recently celebrated the completion of the south transept in an impressive way, but nothing on the scope of the tower dedication had been attempted prior. New works were commissioned from Samuel Barber, Ned Rorem, Lee Hoiby, Stanley Hollingsworth, Roy Hamlin Johnson, John LaMontaine, Milford Myhre, and Leo Sowerby. A two-LP album of the music, dramatic narrations by Basil Rathbone, and a book containing the scores of the commissioned music commemorated the event, all produced under Wayne’s careful direction.

Wayne was asked to chair the committee planning these festivities. In order to do that he relinquished his position as Associate Organist and Choirmaster in 1963. Those duties were assumed jointly by Norman Scribner, who would go on to become a renowned choral director in Washington, and David Koehring, a Fellow of the new College of Church Musicians.

Following the widely-reported success of the tower dedication festival, Dean Sayre pondered the whole concept of the cathedral’s “program.” Up to this point the actual building of the cathedral, together with ordering of regular and special services consumed the cathedral’s efforts—that was its program. The three concerts offered by the Cathedral Choral Society during the season were the only non-liturgical events offered at the cathedral, and it was decided to invest some discretionary budget into planning a series of offerings on a three-year trial basis which would include all the arts.

For this the cathedral turned to Wayne Dirksen, giving him a new title: Director of Advance Program, a position he held from 1964-1977, though the title was later shortened to Director of Program. The fruits of this new initiative were many and long lasting, including an annual summer festival featuring events of all kinds attracting many celebrities such as Ravi Shankar and Dave Brubeck (The Light in the Wilderness, The Gates of Justice), as well as performances by visiting choirs and ensembles—such as the Renaissance dramas “The Play of Daniel” and “The Play of Herod” performed by the New York Pro Musica under Noah Greenberg, and Menotti’s opera The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore. An annual boy choir festival featuring the new Berkshire Boy Choir and later diocesan RSCM festivals sprang from the initial summer festival. Other community events, such as the Open House in the fall were also begun.

During all of this Wayne continued to compose regularly. He also attracted the attention of search committees at some very interesting and highly visible institutions: he turned down an offer to become the Dean of Oberlin Conservatory, and Grace Church at Broadway and 10th Street in New York approached him about the position of Organist and Master of the Choristers when their renowned organist, Ernest Mitchell, retired. The correspondence between Dean Sayre and the newly-appointed rector of Grace Church, the Rev. Benjamin Minifie, is endearing.

The Dean implores Minifie to look elsewhere, saying that the combination of Dirksen and Callaway is “heaven on earth,” continuing:

I am quite sincere in saying that if either he [Wayne] or Callaway left, the greater part of the joy of being Dean here would leave with them . . . I thank you for telling me of your interest, and naturally I would not stand in the way of anyone so fine as Wayne if he really wanted to go.[13]

Yet he freely admits that the music of Grace Church would flourish should Wayne decide to accept. To those who know these two institutions, it is interesting to contemplate what their programs might have looked like under the leadership of Wayne Dirksen during the 1960s to 1980s.

Precentor and Organist and Choirmaster of the Cathedral Church

In 1969 Wayne Dirksen was appointed Precentor of the cathedral church, though not yet Canon Precentor. It was reported that this was the first time that a lay person had been appointed precentor of a cathedral in the entire Anglican Communion and it was big news! In this position he was in charge of the entire worship life of the cathedral and oversaw several related departments, including music, vergers and sextons, sound technicians, ushers, altar and flower guilds, and visitor services, especially as it related to visiting choirs, and other dignitaries and personalities. In his annual reports to the Dean and Chapter and in his correspondence it is dizzying to review the sheer number of services and persons involved in the various tasks necessary to implement the cathedral’s mission and ministry. In all ways except sacerdotal, Wayne was a member of the senior clergy of the cathedral and was likely the most highly visible layman in the Episcopal Church. Throughout all of this, he continued to compose regularly, and his correspondence shows that more and more he struggled to find the uninterrupted time necessary for that, though in 1969 he relinquished his duties at the two cathedral schools.

With the nation’s Bicentennial in sight, it was decided to stretch the building program to the limit and complete the nave in 1976. Wayne relinquished the duties of Precentor in 1973 and led the committee to plan for the cathedral’s elaborate observances of these two singularly important events. Known collectively as Festival ’76, it included several services and events over an 18-month period on a scale far surpassing the dedication of the tower in 1964. Included were services dedicating the new west rose window, the Sowerby Swell division of the renovated organ, and on the exact 200th anniversary, July 4, 1976, the Dedication of the Nave in the Service of the United States of America. On the following Thursday, in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, and President and Mrs. Gerald Ford there was a festival prayer service. Throughout the remainder of 1976 there were other dedicatory services acknowledging the cathedral’s place in the world-wide Anglican Communion, as well as interdenominational ecumenical services. The planning, implementation, and documentation of all of these services and events were accomplished under Wayne’s supervision.

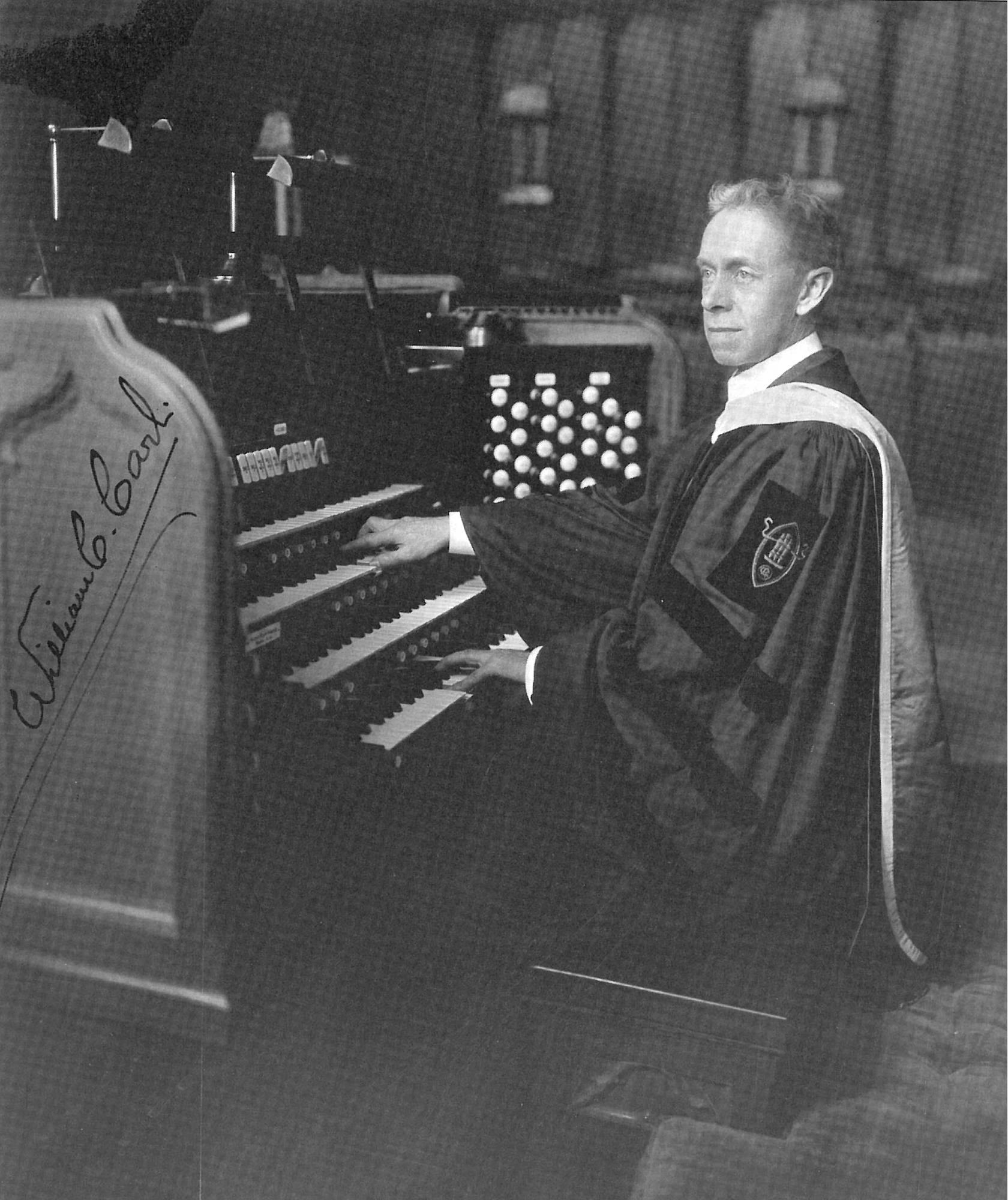

Coinciding with the opening of the complete nave, was the completed renovation of the cathedral organ, an intense three-year process. For this project, planning for which began in 1957, Wayne was the coordinator for the cathedral. Wayne had also directed the installation of the Aeolian-Skinner Organ in Bethlehem Chapel in 1952, and even devised a mechanical device to adjust the pedalboard height, a prelude to the more sophisticated hydraulic lift for the pedalboard on the main organ when the new console was built in 1958.

Wayne had also been responsible for the procurement of two other organs the cathedral used: a completely movable organ with attributes and uses similar to the famous “Willis on Wheels” in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. This organ was built by Reuter, but the casework was built by Wayne’s father, Richard Watson Dirksen, known to the family as “Dugan.” The other organ was a small portative fabricated by the elder Dirksen’s Freeport Organ Company with pipes made by Aeolian-Skinner, which saw use as a continuo instrument in concerts.

When Paul Callaway retired as Organist and Choirmaster in 1977, Wayne was appointed the fourth Organist and Choirmaster of the cathedral. The position of Precentor had recently fallen vacant and Wayne was again appointed to that position as well. Throughout all the varied activities and events he oversaw, Wayne continued to compose, including works for the new Episcopal Book of Common Prayer and Hymnal 1982, including six hymn tunes, two Anglican Chants, and challenging anthem settings the Three Songs of Isaiah, which canticles were new to the BCP. These were given their first performance in Washington Cathedral, during the national convention of the American Guild of Organists by the Choir of St. Thomas Church in New York, directed by Gerre Hancock.

Canon Dirksen, Completion of the Cathedral, and Retirement

In recognition of his 40th year of service to Washington Cathedral, the chapter named him Canon Precentor, and he was installed as a canon of the cathedral in 1983. At the service, during which other ordained clergy were seated as canons, there were only two lay canons installed, and Wayne shared the honor with Richard Feller, the cathedral Clerk of the Works.

Even though he retired from the cathedral in 1977, Paul Callaway continued to direct the Cathedral Choral Society until he retired from that position in 1984. Wayne was appointed interim director of the CCS while a search for a permanent director was undertaken. Over the years Wayne had been closely related to the CCS and served it in a variety of capacities, including accompanist, assistant director, and business manager. J. Reilly Lewis, a graduate of Oberlin and Juilliard, who had begun his career as a member of the cathedral’s Junior Choir under Wayne, was appointed and he served until his death in 2016.

Other honors accrued to Wayne in his final years at the cathedral. He received honorary doctorates from George Washington University and Mount Union College and honors from Peabody and Shenandoah Conservatory. He served a residency at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific in 1987, and commissions continued to be offered.

Wayne resigned as Organist and Choirmaster in 1988 to lead the cathedral in its plans to consecrate the completed cathedral. He was succeeded by his associate, Douglas Major. The festivities observing the completion of the cathedral culminated in a marathon series of services and concerts over the 48-hour period of September 28-30, 1990, and included appearances by President and Mrs. George H. W. Bush.

Wayne Dirksen retired from the cathedral the following spring; the official service marking this was held on April 1, although there were many events on the cathedral close honoring him. In retirement, Wayne was active and in demand. He was a guest at the Evergreen Music Conference in 1993 and continued to compose. He began setting much of his music in computer notation and published an annotated catalog of his music. Dirksen’s hymns tunes were the subject of an article by Clark Kimberling in the October 2002 issue of Journal of the Hymn Society

Wayne’s beloved wife Joan Shaw died on January 27, 1995. Richard Wayne Dirksen died July 26, 2003 and his memorial service was held in the cathedral on August 28. They are each interred in the columbarium of the cathedral crypt adjacent to the Chapel of St. Joseph of Arimathea.

In 2006 the Cathedral Choral Society established the Dirksen Endowment Fund which sponsors its Third Millennium Christmas Carol Commissions.

Conclusion

Within the space limitations of this article, it’s been a challenge to chronicle the activity of Wayne Dirksen’s life. As a result, nothing has been offered pertaining to the mental acuity or personality manifest in his extraordinary creative life. Fortunately, Wayne’s concluding remarks at the aforementioned AAM gathering gives us an important clue:

I conclude these remarks with a quotation that has been of greatest theological influence in my creativity. Louis Pasteur wrote: “The Greeks understood hidden power of things infinite. They bequeathed to us one of the most beautiful words in our language—the word ‘enthusiasm’—en Theos—a God within. The grandeur of human actions is measured by the inspiration from which they spring. Happy is he who bears a God within and who obeys it. The ideals of art, of science, are lighted by reflections from the infinite.”

My succinct perspective is this: when people perform music together, that enthusiasm within each engenders a community-wide awareness of those reflections of the infinite. The sharing of “a God within” through making music puts us in unison touch with the infinite God, and intensifies our knowledge of and enthusiasm for Him. Collectively, therefore do we embody and live our theology.[14]

Part II—Compositions

Introduction

It’s not known exactly when Wayne began to seriously compose. Following high school we know by his own account that he studied theory with Hugh Price, in addition to piano and organ. Biographical references also state that he did not study composition (or conducting) at Peabody.

We also know that, in addition to his keyboard study, he played the bassoon in his high school band and won a statewide solo competition playing that difficult instrument. Looking back at his body of compositions, it’s clear that he was very effective in writing for wind instruments, significantly more so than is typical of keyboard-centric composers.

Dirksen may have had the occasion to show some of his compositions to well-known composers passing through Washington. We know that he played his organ sonata for Leo Sowerby and Sowerby’s reply was that he could correct or suggest this or that, but that Wayne was advanced to the point that he could fix it for himself. It’s not an exaggeration to say that he was self-taught as a composer—and as a conductor, for that matter.

His earliest surviving manuscript is an ink copy dated June 1941 which is included in the notebook he used for his studies at Peabody. It is a solo setting of a poem by John Greenleaf Whittier titled “Benedicite.” Not to be confused with the Prayer Book canticle of the same name (a setting of which he later did compose), it reads:

God’s love and peace be with thee, where

So e’er this soft autumnal air

Lifts the dark tresses of thy hair.

The poem continues for twelve more stanzas of three lines each, concluding:

With such a prayer, on this sweet day,

As thou mayst hear and I may say,

I greet thee, dearest, far away!

Wayne sets the complete poem and dedicates it “To Joan,” his high school sweetheart from Freeport, Illinois, who became his wife.

Links to scores and recordings of most of the works mentioned in this article are located on the timeline on the Dirksen Centennial website, together with an interactive account of Dirksen’s many other activities: Timeline | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

Of particular interest are 1) Wayne’s own annotated catalog of his compositions composed during his tenure at the cathedral, which he compiled in his retirement;[15] 2) Two academic works by Fr. James Moore;[16] and 3) Clark Kimberling’s article in The Hymn.[17]

Characteristics of Dirksen’s Compositions

Dirksen composed some 300 works of great variety of style, for varying forces and occasions, almost evenly divided between sacred and secular. Wayne said in jest that he was an “occasional composer,” meaning that he wrote for a specific event: a commission, a family wedding or funeral, or a cathedral observance or dedication. In fact, Dirksen states that of the many first performances of new compositions that Paul Callaway undertook in his long tenure at the cathedral, half of them were composed by Wayne himself.[18]

It is true that Wayne composed as the result of a need or request, as opposed to some inner muse to compose for the sake of composing. When considering his other performing, teaching, and administrative duties, it is remarkable that he found the time to compose as much as he did. When reviewing the dates of his compositions alongside his biographical timeline, it is easy to recognize those years when he composed less than previous ones, but he did compose regularly throughout his tenure at the cathedral.

In Part I we learn, in Wayne’s own words, the significant impact that the cathedral space itself provided in terms of his own compositional inspiration. The primary impetus for his compositions was indeed the need/ask, and the ever-expanding space of the cathedral as it was being constructed. In fact, in his annotated catalog he began with an aerial picture of the cathedral as it appeared in the 1940s and concluded with a similar aerial shot of the completed cathedral. He literally grew professionally as the cathedral grew physically—a unique position in the history of each.

Speaking in 1998, as he reflected on his life of music at the cathedral, Wayne said:

It has two great powers, music in the Cathedral: the power to instill a mystical quietude with searching intimacy, or the power to overwhelm and shape with emotion – the gamut between the Incarnation and the Resurrection. What a space to occupy with music![19]

In reading others’ essays on Dirksen’s music, or when discussing it in person, inevitably there emerges a list of composers whose works may have inspired Wayne’s compositions, names such as Stravinsky, Hindemith, Bartok, Walton, Kurt Weill, or William Mathias. One could argue the relative merits of each of these and add or subtract to the list ad infinitum.

One of Wayne’s “other duties as assigned” was to be the rehearsal accompanist for the Cathedral Choral Society. As such he had a performer’s knowledge of an eclectic cross section of choral repertoire, including a lot of contemporary music by these very composers, plus Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, andBernstein’s Chichester Psalms shortly after each were written. Also included in CCS concerts in the 1950s and early 1960s were significant works of Frederick Delius and Leo Sowerby, and it is interesting to note that Dirksen’s music bears little overt homage to that lineage of musical composition.

On February 26, 2021 the cathedral sponsored an online festival observing the 100th anniversary of Dirksen’s birth. Included was a discussion at which several people spoke, including George Steel, a former Dirksen choirboy who is now the Abrams Curator of Music at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. George later expanded on his thoughts:

One of the lessons I learned early on in my musical training under Wayne Dirksen was that liturgy is theater, and that liturgical music, therefore, is site-specific theater music. (Theologians might quibble, I suppose, that traditional theater is a kind of representation, whereas the liturgy is “the thing itself.” I might argue otherwise.) To my young self, Wayne underscored this idea of liturgy-as-theater, and of the Cathedral as a stage-set in which to enact music dramas of every scale.

The scholarship current in the 1950s posited that Drama in the West was reborn following the Dark Ages out of a simple three-line Easter responsory (the “Quem quaeritis”), which subsequently moved out of churches as it was elaborated into full-fledged theater. Under Wayne’s Precentorship, that evolutionary connection from versicle and response to full operatic exchange was on regular display. Participating in Wayne’s carefully made liturgies, whether simple memorial services or his fully composed liturgical dramas, made clear how thoughtfully he was structuring a series of dramatic events, ever conscious of the emotional and spiritual impact of each gesture: the tolling of the bourdon bell, the sounding of the Trompette-en-Chamade, the juxtaposition of chant (or chant-like music) and through-composed music, a procession, a station, a meditation, a congregational hymn. In liturgy, music is always an action.

Dirksen’s work bore the clear imprint of his fascination with works like Play of Daniel and the York and Chester mystery plays, which were revived mid-century. And he was part of that wave of musicians who responded in kind: Stravinsky, with The Flood and other works; Britten with Noye’s Fludde and his chancel operas, and Menotti’s neo-medieval The Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore.

Dirksen went further, writing and staging actual theater works and operas in the Cathedral. In fact, the first opera I ever saw in person, Menotti’s Martin’s Lie, was staged in the Nave under Wayne’s tenure. That production taught me three wonderful things I took (erroneously) to be givens about operas: that they should be new works, they should star choirboys, and they should be staged in Cathedrals. In 1981, when I worked on the revival of Leonard Bernstein’s Mass at the Kennedy Center—a work that is literally liturgy-as-theater—I saw further proof of ideas that I had absorbed already from Wayne. Of course, Wayne had played the world premiere of Mass, which had had a seismic effect on him. And, I see now, that through Wayne, I learned some of what he had learned from Mass, before I ever saw it.[20]

There’s a dissertation topic for the taking in a complete theoretical analysis of Dirksen’s works. What follows are but introductory observations:

Wayne’s early song referenced above is simple by comparison with many of his later compositions, even those for solo or unison voices. Still, there are clear early indications of characteristics that would later define his compositional style, such as 1) wanderings into key centers other than so-called closely related keys—and a return to the original key in a comparatively short period of time, 2) predominantly linear writing with memorable melodic content, and 3) an independent keyboard part, or instrumental accompaniment of comparable linear interest.

These three traits are present in most of Dirksen’s works in gradually advancing ways, but the linear unfolding is a dominant compositional trait throughout. Strictly speaking, there’s relatively little formal contrapuntal or fugal writing in most of his works. The vocal canons, by definition, are obvious exceptions. But there is nothing in his music reminiscent of the static, homophonic texture of Lauridson or Pärt that luxuriate in the sound of a prolonged homogenous choral sound, even in his hymns, the best-known of which are in fact unison tunes with accompaniment.

In general Dirksen’s music is characterized by mixed meters, which bring about lively or “sprung” jaunty melodies, such as the Benedicite omnia opera from The Fiery Furnace or Hilariter, or to notate a flowing chant-like tune such as Innisfree Farm.

Regarding harmony, key centers tend to be audacious in the juxtaposition of distantly related material which reverts back to the original point of origin very quickly. This is particularly obvious in most of his hymn tunes. Modal influences and other non-diatonic pitch sets, such as the octatonic scale, are also common.

Dynamics tend to be wide ranging with sharp contrasts, especially so when accompanied by instruments and percussion, and climaxes are punctuated and released effectively, and often several times in sequence before the obvious main climax. In terms of form, common elements are strophic chorus/verse, classic ternary and rondo, and dance forms such as the Sarabande and Galliard.

In terms of instrumentation it is clear that Dirksen is skilled at writing for wind instruments, particularly woodwinds, which is not surprising given his early mastery of the bassoon. Individual independent linear lines dominate the texture. Even in his choral works with organ accompaniment, the organ part often bears more resemblance to instrumental writing, as opposed to a keyboard-centric texture. As a result they are often quite difficult and performances assume the services of a skilled organist.

Brass fanfares, both as stand-alone pieces and as introductory passages to other works, are almost ubiquitous and are clearly a response to the cathedral space itself.

A unique and fairly consistent characteristic of Dirksen’s instrumentation is the use of bells. In Part I Wayne’s involvement in the procurement of the cathedral’s bells—the ten-bell ring and the carillon—is described. The cathedral also had a set of Whitechapel handbells duplicating the pitches of the ten-bell ring in the tower, diatonic D major, D-F#. These were ostensibly for the purpose of practicing change ringing, but they were kept in the choir room and often saw use in Wayne’s compositions, and in the changes that accompanied the singing of plainsong psalms in procession.

In addition to calling for actual bells in his instrumentation, he also used change patterns melodically in some of his pieces, such as the conclusion of Sing Ye Faithful, which quotes the Queen’s Change as a prominent backdrop to the concluding main theme. His 1950 organ sonata includes bell-like gestures, long before the cathedral bells arrived.

An Overview of Dirksen’s Compositions

What follows are logical “chapters” in Dirksen’s compositional life, which are marked by actual events in the construction of the cathedral.

1942 Beginnings

When Wayne arrived the main worship space of the cathedral was the Great Choir, Sanctuary, and High Altar. Initially a temporary chancel had been set up in the sanctuary and individual chairs were arranged in the Choir facing the altar. By 1942 the choir stalls had been built, but the marble floor was yet to arrive. The North Transept was complete and there was enough of a Crossing to connect it to the choir, but its roof had not yet risen to the level of the vaults.

Robert Quade, who studied with Paul Callaway from 1947-1952, remembers the edifice:

Several hours alone in the mysterious beauty of stone and carved wood would bring supreme thrills. Metal ceiling to the Crossing, no bays to a Nave, and the South Transept was under construction! The plastic coverings of the South Transept windows would often allow sweet doves to enter and fly about the Great Choir. Only once, as I was leaving, did a feathered fowl alight on my shoulder—I remember wondering about the symbolism![21]

One of Dirksen’s most enduring anthems was written during this time frame, his well-known setting of the Easter Canticle Christ Our Passover. In Wayne’s annotated catalog he lists this anthem as coming from the 1960s, and that is indeed when it was published. It was actually sung for the first time as the Gradual at the 11:00 service on Easter Day 1948.

It is interesting to contrast this epic anthem with Dirksen’s 1950 compositions for “Faith of Our Fathers,” the outdoor drama produced by Paul Green for the opening of the Carter Baron Amphitheatre in Rock Creek Park. They are each vivid and dramatic, but one was obviously intended for sacred use, and the other, secular. Chanticleer was composed for the Christmas Day broadcast in 1950.

Dirksen’s first commission was in 1954 resulting in the anthem For this Cause; the Canons on Psalm 101 followed. One of his most popular works, the Christmas Carol A Child My Choice, followed in 1955.

1957 50th Anniversary of the Laying of the Foundation Stone

Welcome All Wonders and Yet even now saith the Lord was written for the occasion. In 1958 Wayne wrote his oratorio, Jonah, for the schools’ glee clubs and orchestra, combining elements of the Biblical story and Melville’s Moby Dick in a libretto by Day Thorpe, who was the music critic of the Evening Star newspaper, and who (along with Paul Callaway) was a founder of the Opera Society of Washington (now the Washington National Opera). Jonah was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. Hilariter followed in 1960.

1962 Dedication of the South Transept and 1964 Dedication of the Tower

The Fiery Furnace | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

It’s hard to imagine the visual and sonic impact that the opening of the South Transept had on theinterior space of the cathedral. For the first time one could stand in the crossing and the vistas to the North, South, and East would look as they do today.

For this occasion Wayne composed his cantata The Fiery Furnace with the intent that the full interior space of the cathedral be used. In his annotated catalog he devotes almost two full pages to describing the work, the forces required to perform it, and the dedicatory service itself. During the prelude the full 200 voices of the Cathedral Choral Society processed to the eastward bays of the Great Choir, and the 100 voices of the combined glee clubs of St. Albans School and National Cathedral School for Girls processed to the North Transept Gallery. During the opening hymn the Cathedral Choir of Men and Boys and clergy officiants processed to their normal place in the Great Choir for the office of Evensong.

Following Evensong and the sermon by the Dean of Coventry Cathedral, the cathedral choir and clergy formed a procession and made their way to three stations for prayers and responses, following which the cathedral choir, directed by Paul Callaway, made its way to the new South Transept gallery. Wayne picks up the account in his annotated catalog:

Three powerful unison trumpet calls sounded in the North balcony and were immediately echoed by an orchestral statement in the South. The reverberation was gathered up in a powerful organ chord that fired off the two hundred voices of the Cathedral Choral Society singing “Nebuchadnezzar the King made an image of gold!” It was instantly heard that the opening of the South Transept space had made a dramatic and beautiful increase in the acoustical dimension of the cathedral.[22]

This work uniquely displays Dirksen’s compositional raison d’etre—occasion and the cathedral edifice. Probably more than any of his compositions, The Fiery Furnace is in fact building specific, although Ronald Arnatt did mount a performance of it in the Art Museum of St. Louis for the triennial convention of the Episcopal Church in 1964. To mark the 50th anniversary of the South Transept in 2012 Jeremy Filsell directed a complete performance with Cathedral Voices, a volunteer group that included some members of the cathedral choir, with the accompaniment provided by organist Scott Dettra. The Benedicite omnia opera Domine from it has been excerpted a few times, including for the 1964 dedication of the central tower, and later on the occasion of the dedication of the Pilgrim Observation Gallery.

I have a personal reminiscence of this work. My parents moved to Washington in 1959 when I was six years old. In the ensuing years they took me regularly to the usual sightseeing venues and I vividly recall one Saturday afternoon we went to the cathedral. There was lots of music going on. Security and crowd control wasn’t what it is today, and we wandered up into the South Transept gallery where a group of singers and some instrumentalists were rehearsing, led by this small but imposing man who kept going over and over a spot featuring just the tambourine.

Many years later I realized we had stumbled on the dress rehearsal of The Fiery Furnace at the very spot where the Benedicite omnia opera begins, and the small man conducting was none other than Paul Callaway. For the performance Wayne Dirksen directed the schools’ glee clubs in the North Transept, and Norman Scribner directed the Cathedral Choral Society in the Great Choir, and Ronald Rice played the organ for the service . . . and for The Fiery Furnace . . . and the solo organ recital that followed!

1976 Bicentennial and the Completion of the Nave

1976 Dedication of the Nave / Festival ’76 | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

To observe the nation’s 200th birthday and the completion of the Nave, the cathedral mounted twenty-eight special events over an 18-month period, all under the imprimatur Festival ’76. These included separate large-scale services observing the cathedral’s local, diocesan, national, and international roles, including a service on July 8 in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, and President and Mrs. Ford.

Wayne had administrative and programmatic oversight over the entire Festival ’76. In addition to that, for the Summer Festival that year he composed music for The Ballad of Dr. Faustus, an original production of Christopher Marlowe’s “The Historie of the Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus.” The work was produced by Ted Walsh and his Shakespeare & Co. in the Crossing of the Cathedral for five performances, August 4-8, 1976.

1990 Completion and Dedication of the Cathedral

1990 Completion and Consecration of the Cathedral | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

The years following the Bicentennial until the completion of the cathedral were some of Wayne’s least productive in terms of composition—there simply was no time. Following the retirement of Paul Callaway in 1977, Wayne assumed the position of Organist and Choirmaster, and Precentor. Directing the daily choir rehearsals, playing the organ, and administering the entire worship department of the cathedral was a herculean task in itself.

Also, following the construction expense to complete the Nave and the costs associated with Festival ’76, the cathedral was broke. Staff was cut, and those remaining did double, and triple duty as needed. There weren’t many festival services, and even the Consecration in 1990, though entirely appropriate to the occasion, was scaled down by comparison with Festival ’76.

Notable among Wayne’s compositions during this time are those occasioned by the new prayer book and new hymnal of the Episcopal Church. For the Hymnal 1982 Wayne is represented with six hymn tunes, including Innisfree Farm and Vineyard Haven, the latter usually being included in a list of the most important hymn tunes of the 20th Century. Fr. Moore’s article[23] on Dirksen’s hymn tunes provides in-depth commentary on each of his 30 tunes, including accounts of what did and what did not make it into the hymnal and, most interestingly, what almost didn’t make it! There’s also a humorous account of the family cat figuring into the tune name of one of them.

David Schaap and Selah Publishing are preparing a Dirksen Hymnary containing his unpublished hymn tunes to texts old and new for release later this year.

The 1979 Book of Common Prayer provided for three additional canticles appointed for Morning or Evening Prayer, collectively known as the “Three Songs of Isaiah.” Wayne composed anthem settings for each of them which are of particular effectiveness. They were composed for the choir of St. Thomas Church, New York, to sing at a service in the cathedral for the 1982 National Convention of the American Guild of Organists. It is unfortunate that these settings are not more widely known, probably owing to the fact that Morning Prayer is seldom sung, and the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis seem to be the preferred canticles at Evensong—plus the fact that they are very challenging. Apart from their liturgical use in the daily office, they are outstanding stand-alone anthems which are especially appropriate for the Epiphany season.

Other Works

Sacred Liturgical Dramas: These include several works on Biblical themes intended for use with the two schools in seasonal services and other events at the cathedral. The earliest is “A Christmas Service” from 1951, and the last, The Raising of Lazarus, is dated 1976. They are all on a par with the similar church dramas by Menotti or Britten.

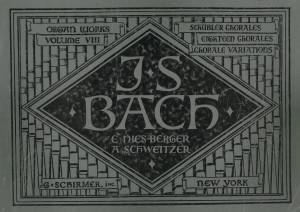

Instrumental and Organ: Dirksen wrote relatively little for his chosen instrument. The “Chorale Prelude on Urbs beata” dates from 1948 and was published by Novello in 1965, Cantilena, the middle movement of his Sonata for Organ, was published by H. W. Gray, and The King of Love hymn prelude was published by E. C. Schirmer in 1995.

Tom Sheehan, the present cathedral organist, has performed and recorded from manuscript the final movement of the 1951 Sonata, and “Much Ado About Nothing—An Overture for Organ” on the cathedral’s YouTube channel. The latter is based on a recorded improvisation based on themes Wayne composed in 1973 for a production of the Shakespeare play in the new theater at St. Albans. Wayne says “Two songs and some incidental music had been written, and upon those sketches I based the overture, improvising with the tape recorder on. It was ‘composed’ in 1992 when putting the songs into computer-engraving.”[24]

Other instrumental works include the Sonata for Clarinet, Strings and Piano; works for various combinations of brass instruments with and without timpani; a suite for organ, trumpet, and handbells; various combinations of works involving harpsichord, guitar, handbells, and various percussion instruments.

Dirksen’s two most significant orchestral works are the symphonic suite created for “Faith of Our Fathers” and a work titled “The American Adventure,” a 38-minute orchestral score composed for a new theatrical production occasioned by the Bicentennial in 1976, which was recorded by professional musicians of the National Symphony Orchestra and replayed at two new, small theaters outfitted with quadraphonic sound and wide screens upon which were projected slides and some motion picture film. “By means of this communications system the history of America was vividly unfolded.”[25]

Works for the Theater: It’s a shame to leave this category to last. It fully deserves a detailed chapter of its own. In studying and playing them we get a glimpse of what Dirksen might have produced in large quantities had he gone to Broadway after the war, instead of returning to the cathedral.

Theater Works | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

I assume that Wayne played lots of secular music in his high school band, and we know he was a DJ on the campus radio station at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he was stationed during the war, where he must have known the popular tunes of the day. He and his team’s offerings were of sufficient interest to have been the subject of the aforementioned story by Meyer Berger published in the New York Times Magazine on December 5, 1943.

Wayne’s most significant works in this genre are in the form of operettas performed each spring at the schools. They are each stylish, full of attractive, memorable melodies, and sophisticated dialog. They were accompanied by Wayne’s brilliant, largely improvised, piano accompaniments. For those directing high school glee clubs, they are well worth considering instead of taking the path of least resistance with yet another Gilbert & Sullivan offering.

Operettas by Wayne and Joan Dirksen | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

Last Works: Wayne was known to have said of his 1995 anthem Sing Ye Faithful, that it was the best he’d ever written. His final work was a setting of the Te Deum, commissioned by Bruce Neswick for the 200th anniversary of Christ Church Cathedral in Lexington, Kentucky in 1996. Each of these works were written shortly after the death of his beloved wife, Joan, and are memorials to her. The conclusion of the Te Deum even includes a quote from a previous anthem, Father In Thy Gracious Keeping, a memorial anthem written for a cathedral colleague, which was also sung at Joan’s memorial service.

Father, in thy gracious keeping | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com)

Conclusion

It’s difficult to summarize or draw to a close these thoughts on the extraordinarily creative life and works of Richard Wayne Dirksen. The Very Rev’d Frances Bowes Sayre, Jr, Dean of the

Cathedral Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington from 1951-1978, with whom Wayne worked so closely, provides two fitting benedictions. The first is from a profile in 1967, when Wayne says:

The Dean phrased it beautifully when I was going through my adjustment period after I stopped working regularly in the music department. (It’s hard when you’ve played the organ for services every Sunday since you were 13 and then you wake up one Sunday and no one needs you!) But the Dean said, “Don’t worry, Wayne, I’m going to give you an organ to play on bigger than any choir or choral society or orchestra you’ve ever had. It’s going to be yours to use, to play on. I trust you.” And he has kept his word.[26]

And, finally, following the success of the tower dedication as Wayne set aside his duties as associate organist and choirmaster, Dean Sayre offered what may well be the most fitting summary of all:

“No man ever wore Joseph’s coat with more imagination than this man of creative devotion.”[27]

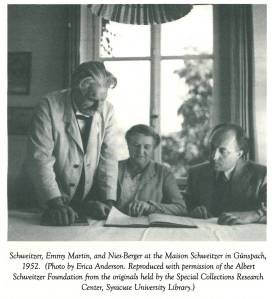

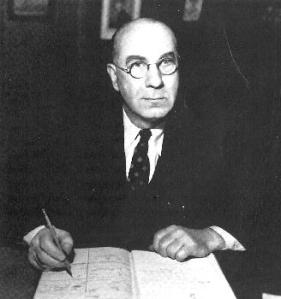

Additional Photographs

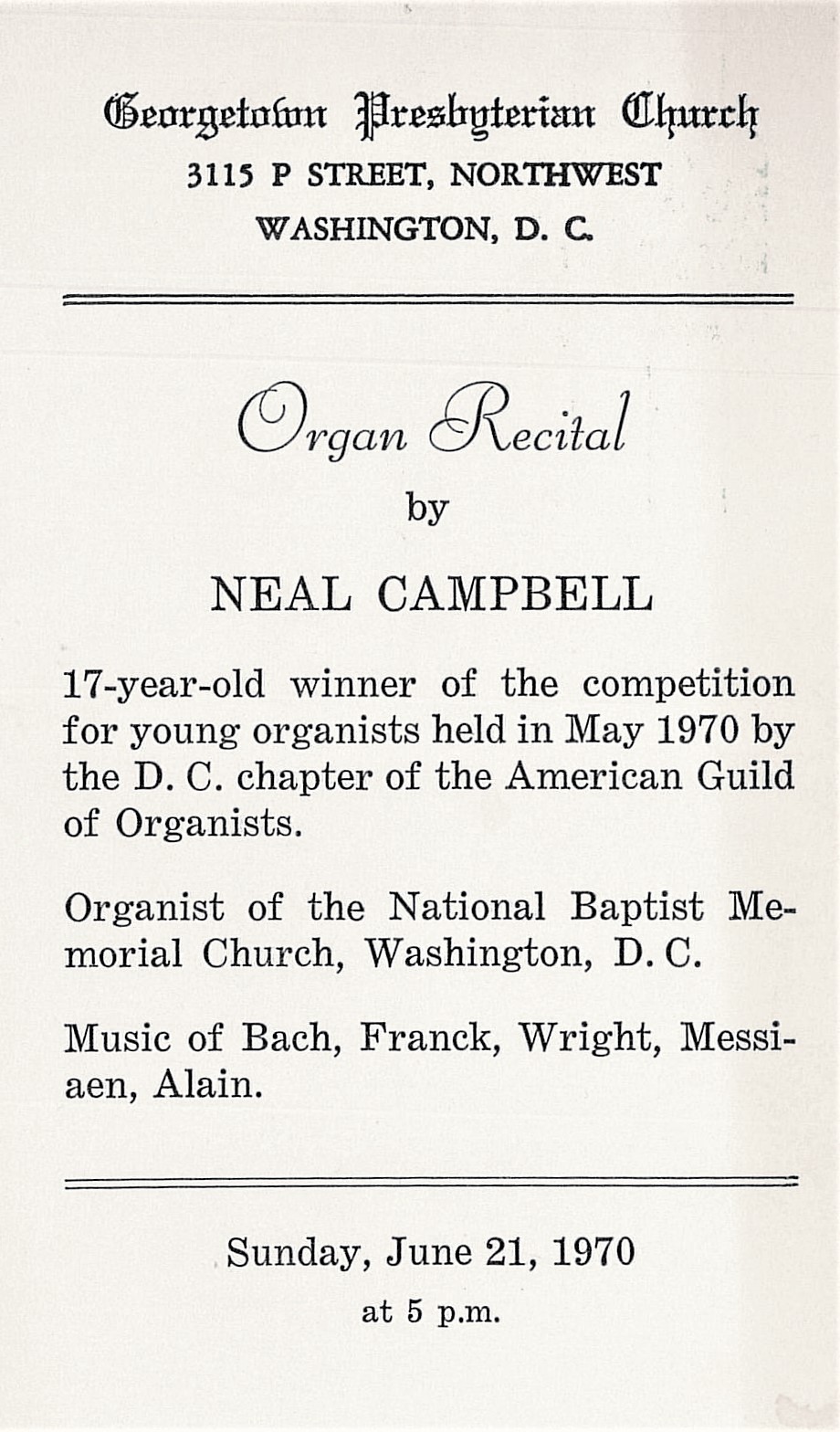

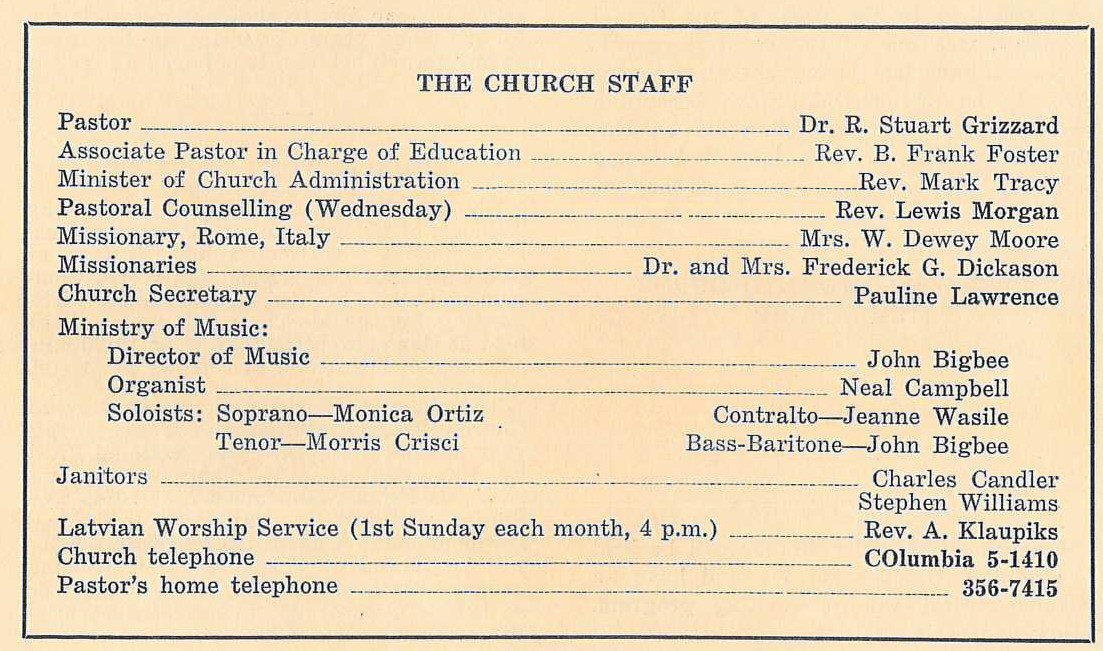

Neal Campbell is the organist of Trinity Episcopal Church in Vero Beach, Florida, following full-time positions in Connecticut, New Jersey, and Virginia, where he was for ten years on the adjunct faculty of the University of Richmond.

He grew up in Washington and studied organ with William Watkins and Paul Callaway. He attended the University of Maryland where he studied piano with Roy Hamlin Johnson, sang in the University Chorus, and studied choral conducting with Paul Traver.

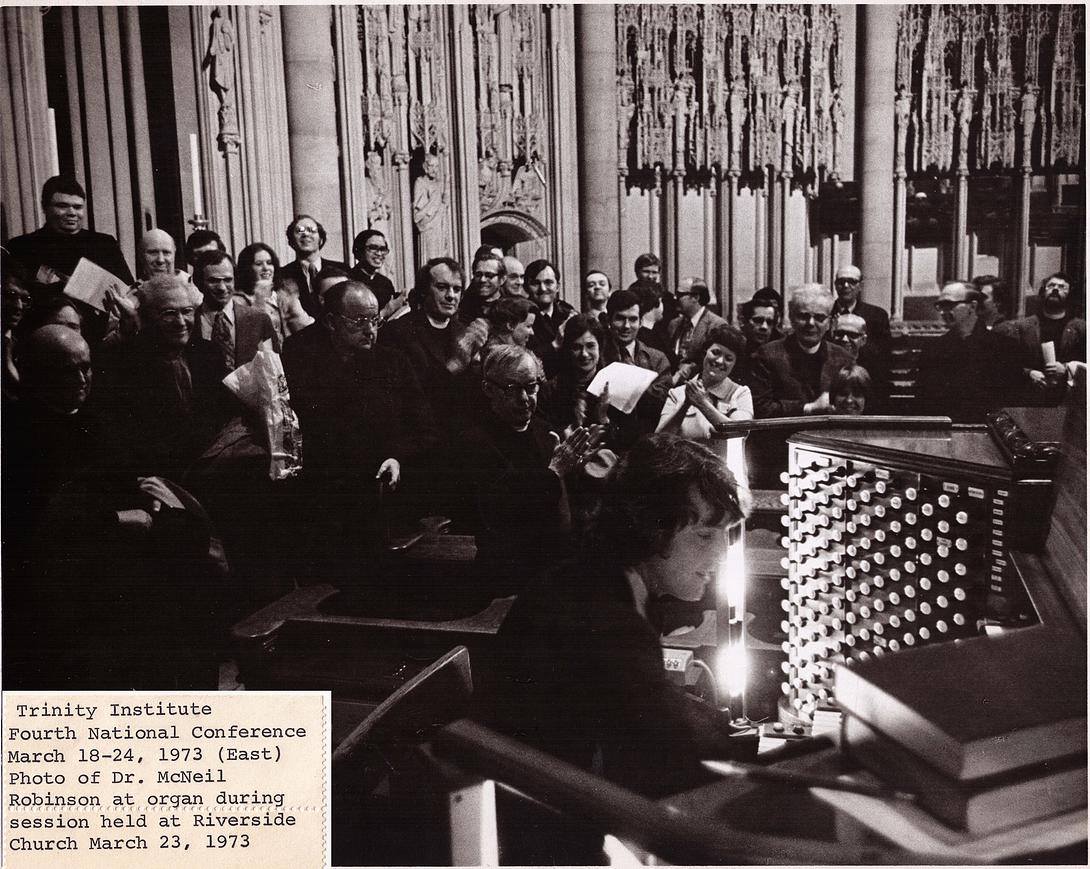

He earned graduate and undergraduate degrees from Manhattan School of Music studying with several leading organists in New York, including Frederick Swann, John Walker, James Litton, McNeil Robinson, Eugenia Earle, Arthur Lawrence, and Alec Wyton. He earned the D.M.A. degree in 1996 and wrote his dissertation on the life and works of New York composer-organist Harold Friedell, and he recorded an album of Friedell’s music which appeared on the Pro Organo label.

He was for six years the editor of the Newsletter of the New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists, and he has written articles published in The Diapason, the Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians, The American Organist, and the Musical Heritage Review. His research interests include New York City musical history, Aeolian-Skinner organs, and other historical topics relating to church music and organs of the recent past. He is currently working on a project about church music in Harlem in the first half of the 20th Century.

His writings are archived at Neal Campbell–Words and Pictures. | Reviews, articles, essays, and photograhs having to do with organs and related topics of church architecture and liturgy. (wordpress.com)

He has served in several leadership positions of the American Guild of Organists, including six years on its national council.

[1] Richard Dirksen, Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians, September 2003, 12.

[2] Family recollections documented on the Dirksen Centennial Website. Family | Richard Wayne Dirksen Centenary (rwdirksen.com). Accessed April 22, 2021.

[3] RWD to his family, February 22, 1942

[4] RWD to his family, March 4, 1942

[5] RWD to his family, April 7, 1942

[6] Meyer Berger, “Good Listening, Quick Recovery,” The New York Times Magazine, Dec. 5, 1943. Archived at LETTERS TO FREEPORT 1942 – 1943.pdf (rwdirksen.com), accessed, April 22, 2021.

[7] Mark Dirksen, ed. “Letters to Freeport: Jo and Wayne Dirksen’s First Years in Washington. 1942-1943.” Family archives, 1989.

[8] Truman Library. Is the letter on display that Truman wrote in defense of his daughter’s singing? | Harry S. Truman (trumanlibrary.gov). Accessed April 22, 2021.

[9] Richard Shaw (Rick) Dirksen, telephone conversation with Neal Campbell, March 15, 2021.

[10] By long-standing tradition the school does not use an apostrophe in its name.

[11] Steven E. Hendricks. “The Washington Cathedral Boy Choir: Musical, Spiritual, and Academic Training of Choristers Through the 20th Century.” DMA diss., Ball State University, 2003. Based on an interview with RWD, 18 May 1999.

[12] RWD profile in The Cathedral Age, Fall, 1967.

[13] The Very Rev’d Francis B. Sayre, Jr. to the Rev’d Benjamin Minifie, Feb. 8, 1960, in the Dirksen Archive of Washington National Cathedral.

[14] Richard Dirksen, Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians, September 2003, 12.

[15] “The Music of Richard Wayne Dirksen Composed at the Cathedral Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Washington in the District of Columbia, Annotated Catalog 1948-1993.” Archived at RWD-Catalog-Complete.pdf (rwdirksen.com) accessed April 22, 2021.

[16] Fr. James Junípero Moore, O. P., “An American Tradition: The Sacred and Secular Music of Richard Wayne Dirksen.” Draft manuscript, unpublished, 2015. Archived at Moore-An-American-Tradition-Music-of-RWD.pdf (rwdirksen.com) accessed April 22, 2021. “Rejoice Give Thanks and Sing! The Complete Hymns of Richard Wayne Dirksen (1921-2003)—Scores and Commentary.” Catholic University of America, 2021. Archived at Moore-2012-Hymn-dissertation.pdf (rwdirksen.com) accessed April 22, 2021.

[17] Clark Kimberling, “The Hymn Tunes of Richard Wayne Dirksen,” in The Hymn, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Oct. 2002), 19. Archived at Kimberling-2002-Hymn-article-1.pdf (rwdirksen.com), accessed April 22, 2021.

[18] Dirksen Annotated Catalog, 41.

[19] RWD speaking to the National Cathedral Association, Feb. 1998. Tape recording, Dirksen Archives.

[20]George Steel, email to Neal Campbell, March 11, 2021.

[21] Robert Quade, email to Neal Campbell, March 8, 2021.

[22] Dirksen Annotated Catalog, 34.

[23] Moore, “Rejoice Give Thanks and Sing.”

[24] Dirksen Annotated Catalog, 22.

[25] Dirksen Annotated Catalog, 23.

[26] “Richard Wayne Dirksen – a Profile.” The Cathedral Age. Fall 1967, 21.

[27] “Report to the Annual Meeting of the Cathedral Chapter.” The Cathedral Age. Winter 1964, 9.

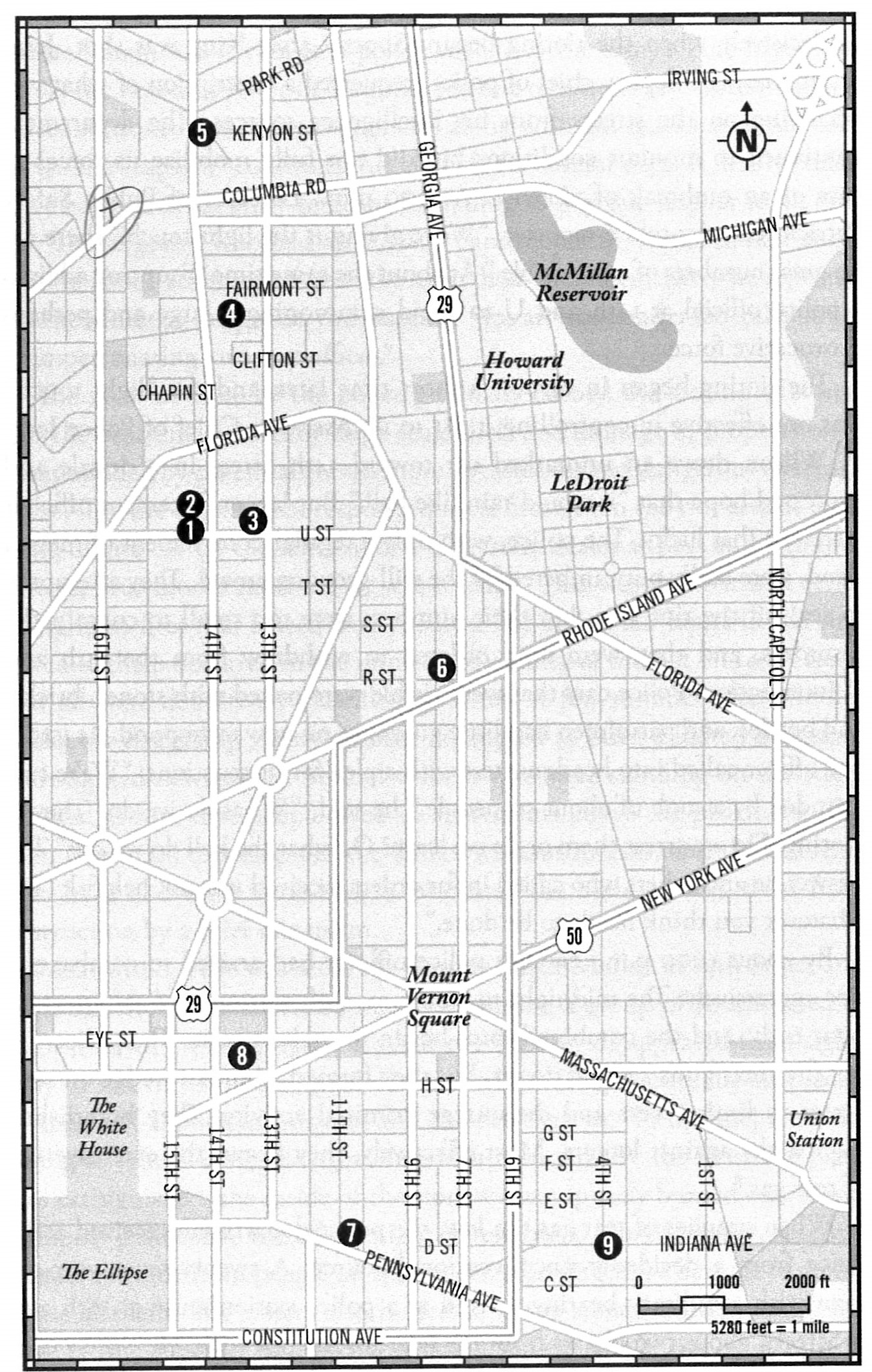

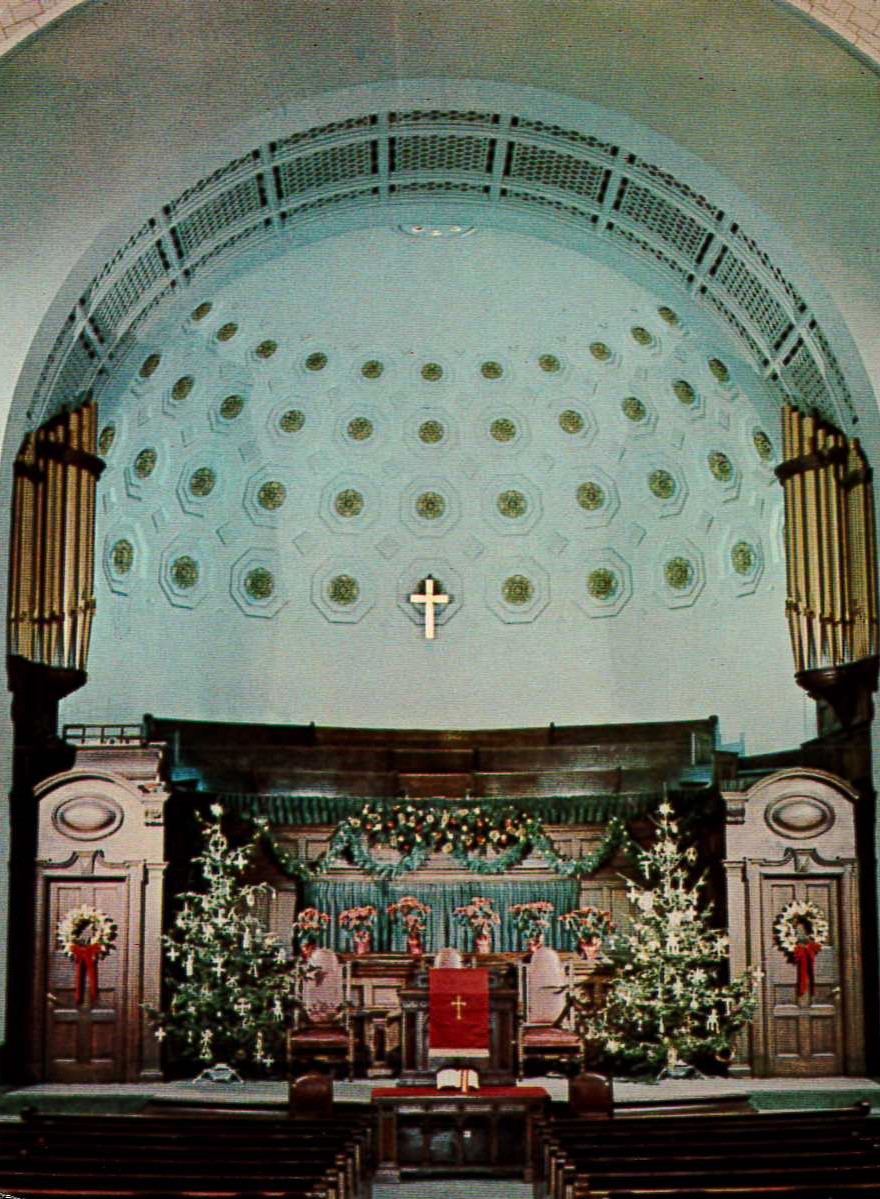

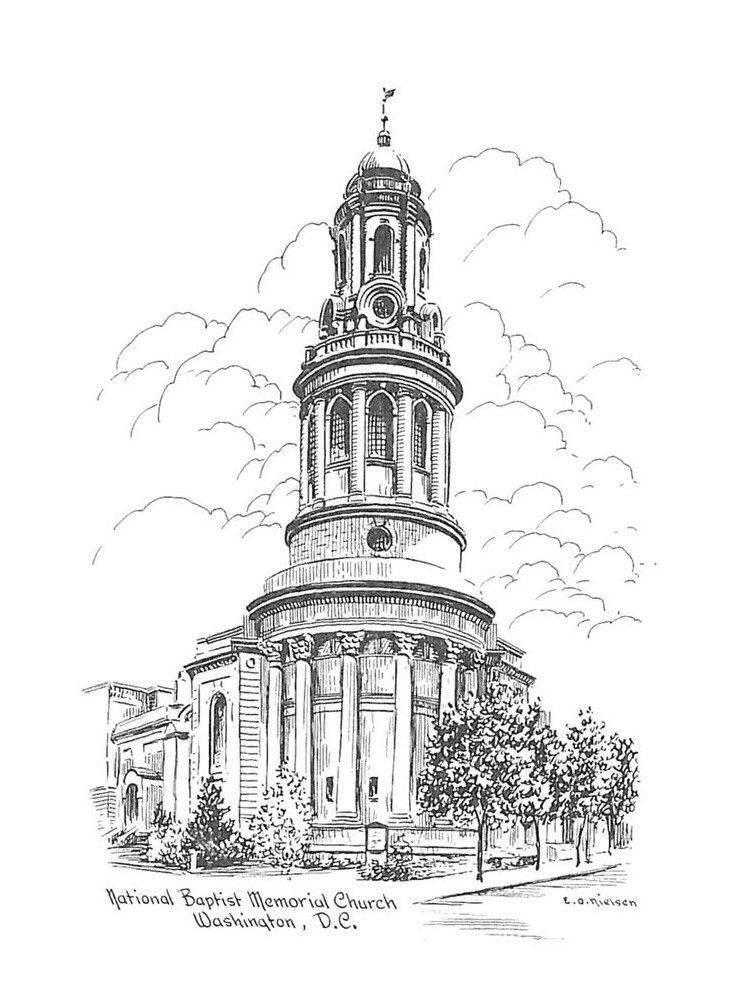

National Baptist is located at a prominent site on Sixteenth Street, just north of Meridian Hill Park at the confluence of the neighborhoods of Columbia Heights, Adams-Morgan, and Mount Pleasant. Its architect, Edgerton Swartwout, formerly of the McKim, Mead & White atelier, designed an imposing tower taking advantage of the triangular site at the top of Meridian Hill created by the gradual incline of Sixteenth Street as it works its way north. As a result of this site location and the architecture of the surrounding area, it is every bit the equal of the more prosperous neighborhoods of Embassy Row or Dupont Circle. At one time I believe it was even planned for Sixteenth Street to be named something more descriptive than its generic numeric appellation. It is a long wide avenue stretching directly north of the White House all the way to the Maryland state line in Silver Spring, and there are many churches of varying denominations, and one or two synagogues along the complete length of the thoroughfare. At Columbia Road, the center of Columbia Heights, there are three churches of significant, prominent architectural interest with spires or towers to match: All Souls Unitarian Church, the former Washington Mormon Chapel (now the Unification Church), and National Baptist. At Meridian Hill Park, just south of Columbia Road, Sixteenth Street takes a dramatic downward incline all the way to the White House. In fact, Meridian Hill Park itself it characterized by an upper park at level grade, and a lower park featuring a fountain feeding into a series of pools descending down the hillside.

National Baptist is located at a prominent site on Sixteenth Street, just north of Meridian Hill Park at the confluence of the neighborhoods of Columbia Heights, Adams-Morgan, and Mount Pleasant. Its architect, Edgerton Swartwout, formerly of the McKim, Mead & White atelier, designed an imposing tower taking advantage of the triangular site at the top of Meridian Hill created by the gradual incline of Sixteenth Street as it works its way north. As a result of this site location and the architecture of the surrounding area, it is every bit the equal of the more prosperous neighborhoods of Embassy Row or Dupont Circle. At one time I believe it was even planned for Sixteenth Street to be named something more descriptive than its generic numeric appellation. It is a long wide avenue stretching directly north of the White House all the way to the Maryland state line in Silver Spring, and there are many churches of varying denominations, and one or two synagogues along the complete length of the thoroughfare. At Columbia Road, the center of Columbia Heights, there are three churches of significant, prominent architectural interest with spires or towers to match: All Souls Unitarian Church, the former Washington Mormon Chapel (now the Unification Church), and National Baptist. At Meridian Hill Park, just south of Columbia Road, Sixteenth Street takes a dramatic downward incline all the way to the White House. In fact, Meridian Hill Park itself it characterized by an upper park at level grade, and a lower park featuring a fountain feeding into a series of pools descending down the hillside.

The organ was Austin’s Opus 1403 containing 42 ranks spread over three manual and pedal divisions, and was built in 1923 for the new church. It was installed in the lower portion of the tower directly above the choir loft. There was nothing especially distinguishing about the sound, but it provided a good variety of stops and was fairly complete. It was my main practice instrument and I learned lots of repertoire on it as I continued my studies with William Watkins and prepared for various student recitals and competitions. Also, preparing the accompaniments for the various anthems, oratorios, and solos required lots of practice time. In a holdover from the past tradition the church employed a quartet of soloists, some of whom were quite good and were generally on the choral scene in Washington. The typical drill on Sunday morning was for there to be a solo and a choral anthem at each service, in addition to hymns and some choral responses. The choir also presented an oratorio once or twice a year and it was here that I first learned Handel’s Messiah, Haydn’s The Creation, and portions of Elijah by Mendelssohn. The organ suited these accompaniments well. Once or twice I had my lessons at the church if I were preparing something special, but by this time figuring out the layout and use of a moderately large organ was not a foreign task for me, and I played as much repertoire as I could for services.

The organ was Austin’s Opus 1403 containing 42 ranks spread over three manual and pedal divisions, and was built in 1923 for the new church. It was installed in the lower portion of the tower directly above the choir loft. There was nothing especially distinguishing about the sound, but it provided a good variety of stops and was fairly complete. It was my main practice instrument and I learned lots of repertoire on it as I continued my studies with William Watkins and prepared for various student recitals and competitions. Also, preparing the accompaniments for the various anthems, oratorios, and solos required lots of practice time. In a holdover from the past tradition the church employed a quartet of soloists, some of whom were quite good and were generally on the choral scene in Washington. The typical drill on Sunday morning was for there to be a solo and a choral anthem at each service, in addition to hymns and some choral responses. The choir also presented an oratorio once or twice a year and it was here that I first learned Handel’s Messiah, Haydn’s The Creation, and portions of Elijah by Mendelssohn. The organ suited these accompaniments well. Once or twice I had my lessons at the church if I were preparing something special, but by this time figuring out the layout and use of a moderately large organ was not a foreign task for me, and I played as much repertoire as I could for services.