This article appeared in an abbreviated form

in the February 2013 issue of The Diapason.

Copyright 2013 © Neal Campbell

Stoplists, photographs, and commentary on the four Aeolian-Skinner organs discussed in this article are found as separate blog entries on the list in the column to the right.

Photographs, most of which may be enlarged by clicking on them, are from my archival collection, internet sources, candids I took via my BlackBerry, and from the Facebook album of Paul Marchesano, which are included with his permission and my thanks.

Background

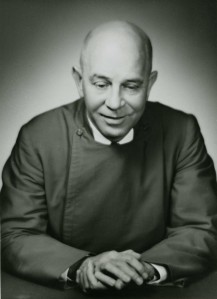

For the second time in as many years I attended the East Texas Pipe Organ Festival held November 11-15, 2012, honoring the life and work of Roy Perry (1906-1978), featuring four organs built by Aeolian-Skinner which he designed and finished. The rationale for such an event is best summed up in Roy Perry’s own words from a brochure he wrote in 1952, describing the organs in First Presbyterian Church and St. Luke’s Methodist Church in Kilgore, and First Baptist Church in Longview shortly after they were built:

Among musicians, only the organist seems to suffer from a chronic indecision in defining his instrument. The pathology of this condition just about parallels the history of the organ, and is perhaps inevitable, since the factors involved in making an organ present a wider latitude of choice than those presented by the piano or the violin. The varying fads and fashions of organ design have had their effect on organ literature; just so has the current repertoire in a given period influenced the thinking of organ designers.

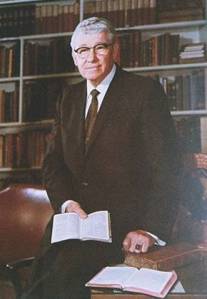

From time to time in the history of this apparent confusion an artist-builder has stood out from the ranks of organ makers to stamp his aesthetic ideals on the organs and the organ music of his era, thus stabilizing for a time a concept of the organ worthy of the respect of musically educated people. Such men were Silbermann in 18th century Germany, Cavaille-Coll in 19th century France, and Father Willis in England. Each of these men, in his own country and his own time, combined a clear historical perspective and a just appreciation of function to produce great, if differing, masterpieces of the organ builder’s art. In 20th century America the man worthy to be named in their company is certainly G. Donald Harrison.

Mr. Harrison is personally familiar with the historical aspects of his art, having examined with a critical ear the best surviving instruments of all periods. Just as a contemporary painter understands the techniques of Da Vinci but refrains from copying Mona Lisa, Mr. Harrison has rejected mere imitation. He has experimented in all styles of organ building, but only to create a style of his own that is eclectic and individual at the same time. It is his expressed aim to create organs on which all worthy organ music can be performed with the highest artistry.

A decade and a half ago the tonal design’s of G. Donald Harrison were considered revolutionary, mostly because of the considerable publicity given a few of his organs built in the so-called Baroque style. At the present time, when tastes range all the way from extreme Romanticism . . . to the bleak austerities of the Baroque, his tonal ideas represent a temperate middle-of-the-road. The flexibility of his thinking is well demonstrated in the three organs considered in this booklet. None of these organs is extreme in any direction. They are alike only by way of family resemblance, but each in its way is a work of art. They provide a generous education in contemporary organ building as interpreted by this great artist, and are happily concentrated in a small geographical area.

It is clear from his own words that Roy Perry considered G. Donald Harrison, and not he himself, to be the designer of these organs. This brings up a question that has sometimes been asked of me: did Perry design these (or any other) Aeolian-Skinner organs? Roy himself would have been the first to say it was GDH, whom he revered during their all-too-brief association which ended when Harrison died in 1956. But it is also true that Roy had a lot of control over the organs he sold for A-S and that GDH relied heavily on his knowledge in setting initial design parameters, especially so in that during the post World War II era the company was at its busiest and Harrison was swamped with inquiries and orders. In the last fifteen years of A-S’s existence following GDH’s death Roy’s influence over “his” organs was even greater, sometimes even surreptitiously so!

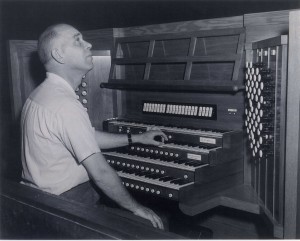

However, the real signature that manifests itself in each of Roy’s organs is the result of the finishing process in which he and the Williams family of technicians brought the factory-completed instruments to their full flower through installing and tonal finishing on site. William Teague, long-time organist of St. Mark’s Church (now Cathedral) in Shreveport, tells of seeing Roy and Jim Williams spend hours on a given stop or pipe to insure its perfect speech, dynamic strength, and blend. Multiplied over the span of his 20 plus year career with Aeolian-Skinner the musical imprimatur on Roy’s organs is hard to miss, although difficult to quantify by means of scientific measurement. Writing to Henry Willis III in 1955 Donald Harrison says that Roy

. . . has supervised, with the aid of Jack Williams [sometimes known as T. J.] and his son [Jim or J. C.], most of our important installations in Texas. He is an accomplished organist and has a wonderful ear. He is a top notch finisher and during my periodic visits to Texas I cannot remember a time when I have had to suggest that something might have been done a little differently. He just has that kind of organ sense.

Festival Itinerary

There are, of course, many examples in this country and overseas of festivals centering on some unifying theme: a composer, musicological practice, or some other cause. Unlike the AGO conventions and denomination specific conferences and their smorgasbord of activities with which I personally have been involved, these East Texas festivals were my first experiences with such topic specific conferences and the rewards for those who love these organs were enormous. The fact that all of the playing was world class and that the organs were in excellent condition made for a memorable week of organ music. [For an account of last year’s festival readers are referred to Michael Fox’s review published in the February 2012 issue of The Diapason.]

As with all conferences, the only way to completely and truly grasp the entire event is to swallow it whole, so to speak, and make it your mission to take in every event in its entirety. My complete participation was somewhat compromised by having to play church in Connecticut on Sunday morning, so I missed the pre-Festival recital by Bradley Welch on Sunday evening in Longview. Further, part of my mission in attending was to provide transportation and note-holding for organ technician Stephen Emery. But I did make all of the recitals on the four featured Aeolian-Skinner organs—the three in Kilgore and Longview, and one in Nacogdoches. And I had the opportunity to play and go through each organ at some length, a great bonus of being the organ tuner’s helper!

Through recitals by a variety of artists these four organs were put through their paces during the festival week and provided an excellent opportunity to see, hear, and compare four distinct, unique Aeolian-Skinner organs that have the unifying characteristic of being installed and finished by the same artisans, Roy Perry and the Williams family. In addition to honoring the legacy of Roy Perry, this year the life and career of Alexander Boggs Ryan, noted teacher and performer from Longview, was also commemorated in the Wednesday afternoon and evening sessions in Longview when the routine departed from its A-S centric (and even its organ centric) scheme in an organ recital and a program of harpsichord music in Trinity Episcopal Church, the Ryan family church and organ. There was also a display of memorabilia on the lives of Perry and Ryan at the Gregg County Historical Museum, and a talk by family members, which I had to miss owing to my note holding duties. Each day also included ample social opportunities at meal times and the nightly “Afterglow” receptions which concluded each day—or began the next morning! I was sorry to have also missed most of these convivial gatherings owing to Steve Emery’s tuning schedule.

Incidentally, just as no discussion of the of these organs in their earlier generation would be complete without mention of the Williams family of organ technicians from New Orleans who installed and maintained them, so the work of Steve Emery was central to the success of this festival. For a week prior to the festival, and throughout the actual week of events, Steve gave these four organs the type of careful, knowledgeable, sympathetic attention that has earned him his high reputation as an expert on the maintenance and restoration of these types of organs. In my personal case, Steve and I worked together for 21 very happy years maintaining and restoring the organ in St. Stephen’s Church, Richmond, Virginia, Aeolian-Skinner’s Opus 1110, an organ of four manuals and 70 ranks which he still maintains, traveling several times a year from his shop headquarters in suburban Philadelphia. In fact, this circuit rider approach to organ maintenance is not unlike what took place in the years following these organs’ initial installations, and on other Aeolian-Skinner installations throughout the region: the Williams— T. J and Sally, Jim and Nora, or some combination—would arrive on site, check into a motel and stay for a week or ten days—once a year at most! to do a thorough tuning and some planned repairs. Between these visits Roy Perry assisted by local organists, choirmembers, and Sonny Birdsong (son Mabel Birdsong, the organist of First Baptist, Longview) would do spot tunings and make minor repairs and adjustments.

Monday

Before the festival officially opened with the evening recital, there was an opportunity in the afternoon to gather in St. Luke’s United Methodist Church in Kilgore for a demonstration of the organ and for some reminiscences and conversation with Charles Callahan and Larry Palmer on composers they had known and with whom they had worked.

Charlie demonstrated the great versatility and color of the organ, one of the larger two-manual organs Aeolian-Skinner built. Of the four organs featured in the festival St. Luke’s obviously has the least favorable acoustical environment for organ sound and Charlie made the point that it was more difficult to build an effective organ in an acoustically dead room, such as this, than in more resonant ones. The organ has always been a favorite of mine and is a notable success within its given parameters.

Larry offered remembrances of his several commissions from and first performances of the works of Gerald Near and Charlie told of his encounters with Leo Sowerby, David McK. Williams, and Thomas Matthews. Of particular interest, however, were his remembrances of visiting with Alexander Schreiner, pupil of Widor and Vierne, who we know primarily as the organist of the Mormon Tabernacle immediately prior to and following the installation of Aeolian-Skinner’s legendary five-manual Opus 1075. But Schreiner’s Ph.D. degree was in composition and he composed a lot of organ music, most of which is unknown.

The opening recital of the festival was given by Thomas Murray at the First Presbyterian Church in Kilgore on Monday evening and was the second annual recital honoring James Lynn Culp, organist emeritus of the church. At the mid point in the evening a plaque was shown honoring Jimmy’s thirty years of service to the church which will be placed in the chancel along with those to Roy Perry and G. Donald Harrison.

Lorenz Maycher, organist of the church and founding director of the festival, made the point several times throughout the week that it was interesting to see and hear first hand how different players approach the same organ. Tom Murray’s use of the organ was the most conservative of the week and the organ obliged completely and effectively in replicating a sound more typical of the house of Skinner in its pre-Harrison days, even in his hefty dose of Bach. The rest of the program, and particularly the Franck was obviously informed by a 19th century aesthetic. In the scherzo, in particular, Professor Murray’s solid and assured technique was put to good use. There was a large crowd, filling the church, including many young people which I was told were from nearby Kilgore College. All told, an encouraging opening to the week.

Thomas Murray, Organist

The Second Annual Recital in Honor of James Lynn Culp, Organist Emeritus

First Presbyterian Church, Kilgore

Concert in C major (in one movement), BWV 595—Bach

Four Sketches for Organ or Pedal-Piano, Op. 58—Schumann

C minor; C major; F minor; D-flat major

Two Welsh Folk-Tune Arrangements—Vaughan Williams

Romanza “The White Rock”

Toccata “Saint David’s Day

Passacaglia, BWV 582—Bach

Intermission—Presentation to James Lynn Culp

Carillon, Op. 75—Elgar

Grande Pièce Symphonique—Franck

Tuesday

The morning recital was again at First Presbyterian Church and could not have been in greater contrast to the use of the organ the previous evening. I had not heard Walt Strony previously, although I had known his name and—erroneously, as it turns out—had assumed he was strictly a theatre organist. What I quickly learned was that his approach, technique, and style sort of defies description in typical academic terms and he seems completely at home in concert, theatre, and church settings. It must have been this type of all-commanding wizardry put to solid musical principles that led throngs to hear Edwin H. Lemare and Archer Gibson in the early 20th century. This was a wonderfully satisfying morning of creative music making.

He used the organ in all of its permutations and possibilities. The standard groupings of organ tone and registration were clearly evident, but the imaginative exploitative quest for color and drama was always also evident, and tastefully so. Walt’s biography in the program booklet says that he has written a book on theatre organ registration which has become a standard reference work for theatre organists. I wish he would write one for classical organists, too. We have a lot to learn from him, especially those who attempt effective transcriptions.

Walt’s program was an eclectic mix of original works for the organ, transcriptions, paraphrases of classical standards, and some dazzling arrangements of his own. His hymn arrangements made me ache for the days when the organ was still the instrument of choice in the evangelistic churches in the pre-praise band era. I particularly liked his inclusion of the arrangement of Fats Waller’s pieces, reminding us that Waller was an organist and knew Dupré! His performance of Lemare’s transcription of the Liebestod easily stood its own with Virgil Fox’s recording at Wanamaker’s. The Carmen Fantasy and closing Kismet suite were organists’ counterpart to a standard 19th and 20th century piano virtuoso’s staple—the symphonic paraphrase. And in this case Walt struck me as being the Horowitz of the organ! Richard Purvis’ music captured the essence of the Kilgore organ which is easily the equal of its slightly older and larger cousin organ, Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, the organ for which Purvis’ music was conceived.

I was impressed most of all by the fact that Walt Strony seemed comfortable in stepping aside and letting the organ take center stage in its own right. He did not try to mold it into his preconceived notion, or filter it through any established aesthetic. He didn’t attempt to make it sound like a theatre organ, or a so-called symphonic organ, or a classic organ, although elements of each were clearly present. It was simply the modern American organ playing music—and, using a word Roy Perry liked to use in describing this very organ, it was “deluxe!”

Someone who had grown up in First Presbyterian Church asked me what I thought Roy Perry himself would have made of the program—a natural question considering that during most of his years at the church (1932-1972), particularly the early ones, Roy was perceived as being strict, even doctrinaire, in his approach to and selection of sacred music. Given the times and lack of any developed religious musical aesthetic in the community, he saw himself as a missionary in paving the way and setting standards of worthy church music, and was often colorfully demonstrative in his opinions of the sacred versus the profane.

But I think Roy would have loved this program. It fully showed off his “banjo” and everyone had a good time. After his retirement from the church most of Roy’s professional life was taken up working on the renovation of the organ in Washington Cathedral which required him to make periodic trips to Washington, sometimes for several weeks at a time. During these visits he always made a point of going to the Alexandria Roller Rink with Bob Wyant, the foreman for the Newcomer firm who took care of the Cathedral organ. Here the very talented Jimmy Boyce presided over a re-installed Wurlitzer and played regular sets to accompany the skaters.

Roy reveled in this flip side of the church organ and was himself a theatre organist at one time. He had been the organist of The Pines Theatre in Lufkin, Texas, before coming to Kilgore. In fact it was Knox Lamb, the manager of the theatre in Lufkin, who suggested Roy Perry to Liggett Crim, the owner of the chain of theatres and also a pillar of the First Presbyterian Church, who was looking for an organist for the new church in Kilgore in 1932. Yes, he would have liked this!

Walt Strony, Organist

First Presbyterian Church, Kilgore

Sinfonia from Cantata #29 “We Thank Thee, O God—Bach

Liebestod from Tristan and Isolde—Wagner

Capriccio on the Notes of the Cuckoo (from Three Pieces)—Purvis

Thanksgiving (from Four Prayers in Tone)—Purvis

Two Hymn Arrangements—Strony

His Eye is on the Sparrow; Joyful, joyful

Intermission

Tico, Tico—Zequinha de Abreu

Carmen Fantasy—Bizet, arr. Strony

Two Improvisations—Strony

Over the rainbow—Harold Arlen; On the Sunny Side of the Street—Jimmy McHugh

Ain’t Misbehavin; A Handfull of Keys—Fats Waller

Bess, You Is My Woman from Porgy and Bess—Gershwin

Medley from Kismet—Borodin ( arr. Robert Wright, George Forrest)

Tuesday afternoon the conference moved to Longview, about a ten minute drive from Kilgore, and was devoted to a visit to Trinity Episcopal Church in Longview, the Ryan family church. Jeremy Bruns demonstrated the Ryan Family Organ built by Ross King, and Larry Palmer played a harpsichord recital featuring several works one is not likely to hear on a recital program featuring this historic instrument—modern works by Near, Howells, Martinu, and arrangements of Duke Ellington—which I was particularly sorry not to hear, but Steve Emery and I had our work cut out for us in tuning the large organ in the First Baptist Church.

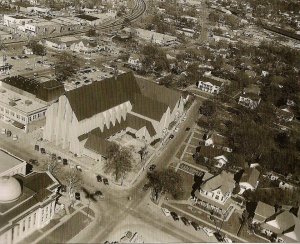

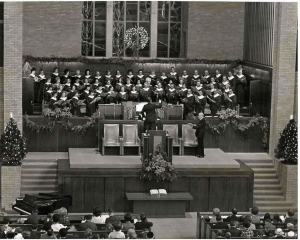

The history and aesthetic of the First Baptist Church in Longview is the stuff of legend. Its complete story is far too rich to adequately tell here. Suffice it to say that as it played itself out, it could only have taken place at the confluence of three important and independent factors: the oil rich location in East Texas, the population boom of the post World War II era, and the visionary leadership of its pastor from 1945-1971, the Rev. Dr. W. Morris Ford.

Unlike some so-called “high” ecumenical Baptist churches in the south with impressive music programs and facilities to match, such as Myers Park in Charlotte, or River Road in Richmond—or even Riverside in New York, First Baptist in Longview was more or less a typical Southern Baptist church. Their services centered on preaching at Sunday morning and evening services, they had prayer meeting on Wednesday nights in the chapel, the men’s bible class met on Sunday before church, and a softball team competed in a church league in the summer. The music was weighted toward participation as a holy offering, as opposed to musical erudition. And, though always courteous and “playing well with others,” they were not overtly ecumenical. The previous church, across the street from the present one, seated some 800 people including horseshoe shaped galleries, and was an American adaptation of a domed classical structure which had served the congregation since 1902. Mabel Birdsong had been the organist since 1920, playing a two manual Hillgreen-Lane organ.

Dr. Ford was a cultured man with an earned doctorate, a love of music, and a fine singing and speaking voice. He sang both as soloist and with the church choir, and it was he that infused the church and its services with an innate sense of classical dignity in all things, which was his authentic response to the calling of the Gospel. This he did without diminishing the essential tenets or manifestations of the Baptist tradition. He brought Dr. Glenn Farr to Longview as the Minister of Music to work together with Miss Mable, who continued as organist until she retired in 1970.

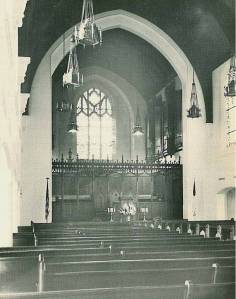

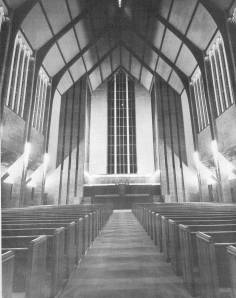

When it was decided to build a new church the vision was big and bold. The local architect B. F. Crain, who trained at Harvard and designed several notable buildings in the area, was selected and the style of the new church was determined to be “Modern Gothic.” To be frank there is little that is Gothic about it in the textbook sense, but the scale and towering spaciousness—even its domination of its local surroundings—is obviously inspired by the Gothic aesthetic stripped to its essential unadorned lines. It seats 1,700 persons, the interior height is 93 feet, and it was designed with the organ’s success in mind from the beginning. Taken in this light, the 87-rank organ seems almost modest, at least on paper. But its tonal impact is comprehensive and monumental. Writing about the organ when it was new Roy Perry says

Although this organ leans toward the Classic style, it affords five pairs of strings, a Vox Humana, and percussions, not to mention the wonderful flutes and small reeds. It will do justice to any music, even the humblest; in grandeur it holds its own with the great organs of the world.

The organ seems to have suited the needs and vision of the church perfectly and was appreciated as an asset to the community and was played by the great organists of America and Europe. Virgil Fox inaugurated the organ and ultimately played there several times, and Catherine Crozier made two notable LP recordings on it which were iconic in publicizing and documenting the organ when it was new. The only reason I can figure why they are not better known is that they were recorded in monaural just before stereo recording technology was coming into its own and they have never been never reissued. And why Aeolian-Skinner never featured this organ on their King of Instruments series of recordings may be one of the mysteries confined to the ages.

In the ensuing years recitals and concerts regularly took place in the yearly round of church services and activities, including a performance of the Bach St. John Passion sung in 1962 by the Robert Shaw Chorale, for which by this time Dr. Ford’s son, David, was a member. The church may not have styled itself as anything but a typical Southern Baptist church, but during Dr. Ford’s tenure as pastor there were many opportunities to be presented with world class music, in ideal acoustical surroundings, by well-known recitalists and ensembles—many more than a typical church of any denomination for miles around. So, although there was a recital here on last year’s festival, it was of particular interest to me that three full-length evening recitals on Opus 1174 were included this year’s activities.

As is typical of most Baptist churches these days in this part of the country, the organ in First Baptist is not now the primary musical instrument used to lead the music of their services; its role is more that of a collaborative player with a band. Impacting the organ’s tuning is a modern computer driven heating, cooling, and ventilation control system which many large spaces rely on these days. By digital means, which are predetermined and programmed into a computer, the heating and cooling systems are used in tandem to create a precise temperature at a precise time. Nothing could be of greater aid in the efficient control of the temperature in so large a building. And nothing could be of greater hindrance in tuning the organ! Steve said that up in the organ chamber heat might be coming out of one vent and cooling out of another in no apparent time pattern, seemingly at random, determined by the pre-programmed computer formula.

The staff of First Baptist were helpful in accommodating the unusual (to them) requests to override the systems for a set period of time to stabilize the temperature long enough for tuning and recitals. The result was that we had to wait for a while until the temperature was approximately that which Steve had left it last. Then, just as it was right, he went to work and all would be well, until such time as the automatic controls took over again. There was a definite window of opportunity for optimum effect, not unlike an immediate flight departure in order to gain a take off spot before a storm prevents your landing slot in a city a thousand miles away. And, according to Steve, we were just barely within that window!

Richard Elliott, organist of the Mormon Tabernacle, played the Alexander Boggs Ryan Memorial Concert at First Baptist Church on Tuesday evening. The recital featured several pieces of varying eras and genres which presented the organ to good effect. Ryan had played at the church in a 1959 program which included several pieces sung by the Rev. Dr. Morris Ford. Three of these songs were here sung by David Ford, and it was good to hear the organ in the role of accompanist, which role was a significant part of the organ’s duty in the normal round of services. Richard played the technically demanding program with the ease and confidence audiences are accustomed to in his weekly broadcasts from The Tabernacle. The concluding work was the familiar Carillon de Westminster, which was characterized by an intense rhythmic drive throughout, and the gradual building up of dynamic forces which continued throughout the piece until the very end—saving something for the final the final few measures. He obviously knew how to elicit the most drama out of the organ. Many an organist wouldn’t be able to resist pulling out all the stops too soon; here the various climaxes were gauged and measured, saving something for the final few bars. It reminded me of the old Columbia recording of Schreiner playing this work at The Tabernacle, and it wouldn’t surprise me if Richard had patterned his scheme from it.

Richard Elliott, Organist

David Ford, Bass

The Alexander Boggs Ryan Memorial Concert

First Baptist Church, Longview

*Chaconne—Louis Couperin

*+Toccata in F, BWV 540—Bach

+The Heavens are Telling, from Six Songs, Op. 48, No. 4—Beethoven

+O Lord, Most Holy (Panis Angelicus) from Messe solennelle—Franck

+Recessional—Reginal De Koven

Cantilena—John Longhurst

Every Tim I Feel the Spirit—Spiritual, arr. Elliott

*Variations sur un Noël—Dupré

*Adagio Cantabile from Symphony No. 3 in C minor—Saint-Saëns

*+Carillon de Westminster (from Pièces de fantaisie, 3ème Suite)—Vierne

Note: Works marked with * were frequently performed by Alexander Boggs Ryan. Works marked with + appeared on the June 9, 1959 recital at First Baptist Church, Longview, featuring the Rev. Dr. W. Morris Ford (father of David Ford) and Alexander Boggs Ryan.

Wednesday

The first event of the day was a delightful program by Charles Callahan at St. Luke’s United Methodist Church which consisted of lesser known gems by Bach, Fiocco, Charles and Samuel Wesley—honoring our host denomination, Peace, Wolstenholme, and three of his own compositions. The program was carefully chosen to highlight the great variety and nuance of this remarkable organ, and was played with charm, grace, and lyricism. I sat in the back of the full, completely carpeted church and the organ had remarkable presence in the room, which itself was completely devoid of reverberation. This is the real testament to the success of the organbuilder’s art.

Charles Callahan, Organist

St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, Kilgore

Prelude and Fugue in C (Misc. keyboard)—Bach

Adagio and Rondo—Joseph-Hector Fiocco

Air and Variation—Charles Wesley

Voluntary in G—Samuel Wesley

Allegro all Marcia—Albert Lister Peace

Pastorale in D—William Walstenholme

Three Pieces—Callahan

Lauda Sion (from Gregorian Suite)

Prelude on Jewels (from Kilgore Suite)

Trumpet Tune (from Suite in D)

Before lunch we walked the few blocks to First Presbyterian Church for Ann Frohbieter’s well chosen program, which, with the exception of Houston composer Michael Horvit’s The Red Sea, consisted of more or less standard organ repertoire. But the playing was anything but standard! Each piece was thrillingly played with an obvious affinity and understanding of the inherent beauty and resources of this organ. To me it was the perfect foil to Strony’s program the previous morning, showing the same vivid approach to the organ via the repertoire.

Ann Frohbieter, Organist

First Presbyterian Church, Kilgore

Introduction and Passacaglia—Reger

Allegro (Concerto in A minor, BWV 593)—Bach-Vivaldi

The Red Sea—Michael Horvit

Variations on America—Ives

Adagio for Strings—Barber

Impromptu (from Pièces de fantaisie, Book III, Op. 54)—Vierne

Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H—Liszt

Program note: The Red Sea. Michael Horvit is a well-known contemporary composer, who for many years was Chairman of the Department of Music Theory and Composition at the University of Houston, and was Director of Choral Music at Congregation Emanu-El. In this composition for solo organ, Dr. Horvit has depicted the Biblical drama of the escape and deliverance of the Israelites from the Egyptians through the Red Sea.

After lunch we walked back to St. Luke’s for a recital by Christopher Houlihan. The program was heroic for so small an organ and room, but consistently well played from memory. It was interesting to hear his interpretation of the Bach Passacaglia on this organ, having heard Tom Murray play it Monday evening and I would have to say that this offering sounded more at home in this setting, than did the other. Houlihan has made a specialty of the Vierne symphonies, playing all six in marathon sessions around the country. He put down three movements from the Sixth, including the Final, but after arriving and playing the organ he substituted three movements from the Second, which was a wise move. I particularly liked the Bach trio sonata and his Debussy transcription, each of which captured an intimate chamber music aesthetic and was ideally suited to this organ and this room. On the whole, the playing was both elegant and exciting. Christopher is certain to have a bright career ahead, and it was good to have someone from the younger generation on the festival roster. Incidentally, there were a good number of young people throughout the festival at individual events, and Joby Bell’s entire studio from Appalachian State University in North Carolina attended the whole week.

Christopher Houlihan, Organist

St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, Kilgore

Toccata—Sowerby

Trio Sonata in C major, BWV 529—Bach

Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582—Bach

Intermission

March on Handel’s “Lift up your heads,” Op 15—Guilmant

Andantino, from String Quartet, Op. 10—Debussy

From Symphony II—Vierne

Choral

Scherzo

Allegro

Wednesday evening was movie night at First Presbyterian Church as Brett Valliant accompanied the silent classic “The Phantom of the Opera.” A large screen was placed in front of the chancel rood screen for the showing of the film and, aside from some opening commentary placing the silent film genre in context for the many younger members of the audience who probably had never have encountered it, the evening was devoted to the sounds of the organ and the visuals of Lon Chaney and the cast in the Paris settings of the Opéra and Notre-Dame. Brett’s accompanying score was lyrical and lush and may have been inspired by the threatre organists of the past, but it—like Walt Strony’s program Tuesday morning—was simply the Kilgore organ rising to yet another musical task with completely satisfying results.

Thursday

Thursday morning we moved to Nacogdoches where the smallest of the four Aeolian-Skinner organs of the festival was featured. The worship space at First Baptist Nacogdoches is slightly larger than St. Luke’s in Kilgore and the factors involving the acoustics are much more favorable, in fact almost ideal: hard wood floors, a minimal amount of sound-absorbing materials and a generous height to width ratio. The entire organ is enclosed in two chambers on either side of the stage-chancel, with openings into the stage-choir loft, and out into the congregation. Greatly enhancing the versatility of the organ is the ability to make the swell shade openings into the congregation operable or not, as desired. The organ is a model of careful voicing, scaling, and finishing, is ideally suited to its surroundings, and is entirely satisfying on its own, in spite of its small size.

The program began with Scott Davis leading the audience in singing a hymn, with his improvised introduction, interlude and concluding stanza. Scott also concluded the program with an extended multi-movement improvisation in the style of his late teacher Gerre Hancock. These—the hymn singing and improvising—were the only nods during the festival to the liturgical effectiveness these organs also possess.The centerpiece of the program was another of Charlie Callahan’s signature programs of interesting, lesser known works which were carefully selected and performed to present the organ in its most favorable light. Charlie also played two recent compositions of his own: Alleluia (an energetic miniature, similar in feel to his more virtuosic Fanfares and Riffs) and Festival Voluntary on “St. Anne” for Horn and Organ which received its first performance.

Charlie also spoke at some length about Roy Perry, Jim and Nora Williams, and some of the other Aeolian-Skinner personalities he has known over the years, particularly Arthur Birchall, for whom as a young man he held notes on tuning and finishing jobs in the Boston area. This was a valuable spoken addition to the basically auditory nature of the week’s events.

Charles Callahan, Scott Davis, Organists

Rebecca Robbins, Horn

First Baptist Church, Nacogdoches

Festival Voluntary on St. Anne for Horn and Organ—Callahan

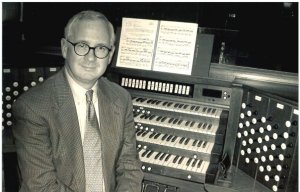

Memories—Clarence Dickinson

Adagio Cantabile (from Cinnamon Grove Suite), 1928—R. Nathaniel Dett

Fireside Fancies, Op 29 (1923)—Joseph Clokey

A Cheerful Fire

The Wind in the Chimney

Old Aunt Chloe

Grandfather’s Wooden Leg

Melody in Mauvre—Purvis

Alleluia (2011)—Callahan

Improvisation—Davis

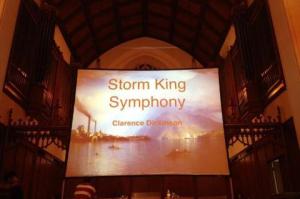

Back to Kilgore for the afternoon recital by Christopher Jennings for what was anticipated as a highlight of the week: a complete performance at First Presbyterian of Clarence Dickinson’s Storm King Symphony, in what was among the first complete performances ever of the entire work. We know that Dickinson played individual movements from among the five, but there is no documentation of his (or anyone else’s) ever playing the entire work, and this was one of several times this season when Christopher has played all five movements in their entirety. The same screen that was used for the movie the previous night remained in place, and Christopher had arranged for still photographs of various scenes to be displayed at the appropriate points in the movements. This was helpful in negotiating the impressionistic, programmatic nature of the work. The program notes told us that the symphony “reflects impressions made on the composer by the varying moods of the stately Storm King mountain, which stands guard, as it were, over the Highlands of the Hudson” near Dickinson’s home.

It is a pity that in most circles Dickinson’s compositions aren’t taken very seriously today. He wrote so many small works and carol arrangements that are so easily accessible that the larger forms such as this, which require significant technical prowess, remain unknown. Taken as a whole, the entire Storm King symphony could easily supplant the ethos of either the Reubke sonata or Liszt Ad nos on a recital program.

Christopher’s use of the organ was informed by the early 20th century organs which Dickinson would have known, but in a commanding and vivid way that did not sound retrospective. The natural power and expressiveness of the organ was entirely satisfying and there was not the impression that he was under-using the organ, even though he elected to leave out most of the upperwork. On occasion he used the famous Trompette-en-Chamade in chorus, Bombarde wise, and it was very effective. The sound is not so ferocious as it looks, at least out in the church. In truth, this stop is one of the standard Aeolian-Skinner Trompette Harmonïque designs mounted horizontally, on reasonable wind pressure, which can, in fact, function as a chorus reed capping the full ensemble when called upon to do so.

I regretted that I could not stay for the second half of the program, which was also by New York composers; Steve Emery and I had to get over to Longview to do further battle with the computerized heating-cooling system at First Baptist Church!

Christopher Jennings, Organist

First Presbyterian Church, Kilgore

Storm King Symphony—Dickinson

Allegro Maestoso

Canon

Scherzo

Intermezzo

Final

Intermission

Fanfare—Alec Wyton

Five Dances—Calvin Hampton

The Primitives

At the Ballet

Those Americans

An Exalted Ritual

Everyone Dance

Toccata—Gerre Hancock

Ken Cowan played the concluding recital of the festival at First Baptist Church. In advance publicity on the Festival’s Facebook page, Lorenz Maycher wrote “on the questionnaire, where his manager asked what kind of program we’d like, I put HEAVY DUTY. That’s exactly what we got. I love it when that happens!” There’s really not a lot that I can add after the fact to that. It was a huge program, played from memory, characterized by effortless technique in the service of the music, and impeccable use of the organ’s vast resources. It was epic and (sorry Virgil Fox) I don’t recall a better organ recital in my life.

I had not heard Ken play his version of the Saint-Saëns” Danse Macabre. It was of the same symphonic paraphrase style à la Horowitz of which I spoke previously when writing about Walt Strony. It was truly astounding, and—fun! Totally new to most in the audience was John Ireland’s Elegiac Romance, an expansive work written for the organ, but symphonic in scope. For his encore, Ken played George Thalben-Ball’s pedal etude Variations on a Theme of Paganini, which—with all due respect—makes the brief Middleschulte pedal etude, which Virgil Fox used to routinely use as an encore, sound trivial.

When the Kilgore organ was new, one of the first players to present a recital on it was William Watkins, who was not yet 30 years old. He had just won the Young Artist Award of the National Federation of Music Clubs—a $1,000 award in 1949—at the time the most prestigious competition to which any young musician could aspire; it was open to all instrumentalists. The competition had been held in Dallas, Watkins was the first organist to win it, and Roy Perry wisely brought him to play the new organ in Kilgore to a full church. The review in the Kilgore News Herald of February 17, 1950, which Watkins used in his publicity for a many years was written by Roy Perry himself, and concluded “This boy is one of the great interpretive artists of the century.” The same can easily be said of Ken Cowan in this century.

Ken Cowan, Organist

First Baptist Church, Longview

Sonata No. 1 in F minor—Mendelssohn

Allegro moderato e serioso

Adagio

Andante, Recitative

Allegro assai vivace

Danse macabre—Saent-Saëns, arr. Cowen

Suite, Op. 5—Duruflé

Prélude

Sicilienne

Toccata

Intermission

Étude Héroïque—Rachel Laurin

Elegiac Romance—John Ireland

Fantasy on the Chorale How Brightly Shines the Morning Star, Op. 40, No. 1—Reger

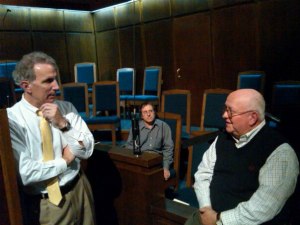

Joby Bell, second from right, and his class from Appalachian State University in North Carolina, at the console of the Longview organ after Ken’s closing recital.

NEAL CAMPBELL has been the Director of Music and Organist of Saint Luke’s Parish, Darien, Conn., since 2006. Prior to that he held church, synagogue, and college positions in Washington, Philadelphia, New York, New Jersey, and Virginia. Growing up in Washington he was a student of William Watkins, and he first met Roy Perry in 1972 when he was a finalist in the AGO National Organ Playing Competition in Dallas, and he continued his friendship with him during the years Roy Perry presided over the work at Washington National Cathedral. He has played and recorded on the Kilgore organ several times.