This article, originally titled Regal Instruments in the Neighborhood, was published in Poco a Poco, the Manhattan School of Music bi-weekly student newsletter, on September 2, 1992. At the time it was the custom for doctoral students to write feature articles each week.

Copyright 1992 © Neal Campbell

As with other facets of our culture, a rather complete history of the art and science of organ-building in American can be traced by studying the organs placed in auditoriums and houses of worship in New York City. Virtually every style and era of organ-building, both foreign and domestic, can be found in our city, dating back to the earliest time of the new colony, when an organ from England was placed in Trinity Church at Wall Street, to elaborate electronic substitutes such as the one installed in Carnegie Hall several years ago, to the retrospective baroque replica in Alice Tully Hall. One important and uniquely American style of organ-building began to emerge in the early 20th century, and this style is also well represented in New York City, and specifically so in our neighborhood here in Morningside Heights.

Ernest M. Skinner (1866-1960) established his own organ-building firm in Boston in 1901, after serving an apprenticeship in several other New England firms. In the early days of electricity, Skinner developed a new type of electric action that was reliable and allowed divisions of the organ to be placed at distant parts of the room. These divisions were connected to a console by means of various electronic linkages. (Keep in mind that before the advent of electricity, keyboards were connected to the pipe chests mechanically. This type of playing action is known as tracker action, or mechanical action.) Skinner, who loved the symphonic and operatic literature, also developed several imitative and evocative stops which yielded beautiful special effects that were popular with the public. Such voices as the English horn, French horn, flauto mirabilis, corno di bassetto, and Erzähler became standard in the Skinner tonal palette. Skinner’s early success in securing large contracts for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and St. Thomas Church on Fifth Avenue assured him a commercial success from the start. From this point onward, the firm built organs for the most prominent churches, cathedrals, concerts halls, and educational institutions. A look at the Skinner opus list reads like a Who’s Who of important institutions in this country, and this near monopoly continued until the company went out of business in 1973.

In late 1927 the Skinner Organ Company took into its organization a young man from England named G. Donald Harrison (1889-1956). Harrison had been a director of the venerable English organ-building firm of Willis and Sons. In reaction to the orchestral organs popular at the time, with their collections of soft color stops and predominance of heavy fundamental tone (all of which were characteristic of the standard Skinner ensemble), Harrison soon became interested in building organs along more classical lines. Scholarship had increased between the two world wars, and several leading American organists had traveled to Europe to see and hear the organs of the historic French and German schools. This had a tremendous impact on Harrison in his desire to produce a unique American organ that would combine elements of the important historical periods with existing Skinner trademarks, such as the beautiful imitative sounds and the reliable electro-pneumatic action. By the 1930s Harrison’s eclectic organs were gaining favor, and many important contracts came to the Skinner Company with specific instructions that the organs be designed by Harrison. Naturally, friction developed between Skinner, who had never altered his ideas of tone, and the progressive Harrison. Ultimately Skinner left the firm and, with varying degrees of success, tried to operate from other headquarters. In the mid-1930s the Skinner Company purchased the residence organ division of the Aeolian Company, and the firm was known afterward as the Aeolian-Skinner Organ Company until it ceased operation in 1973.[1] During its history the company produced about 1,400 organs—not so many when compared with some of the more commercial builders. Continuing interest in these American organs and their prominent locations attest to their superior artistic and technical properties.

In our immediate neighborhood, there exist four rather important organs designed by Harrison at different periods of his work. The oldest of these four is in St. Paul’s Chapel of Columbia University. This organ, Opus 985, dates from 1938 and was among the first of Harrison’s organs to take on the new classic style. It contains two unenclosed baroque divisions on either side of the wide chancel, together with an appropriately developed pedal division to match—essential to playing trio sonatas in particular and contrapuntal music in general. The organ has remained virtually unchanged except for some additions in the dome of the chapel, which Aeolian-Skinner added in the 1960s.[2] Many of the leading organists of the world, including E. Power Biggs, played and recorded on the Chapel organ, and the instrument represented a turning point in the visibility of the new type of “American Classic” organ, as this style had by then come to be known. Before the student riots in the late 1960s, there was an elaborate chapel music program, led by Searle Wright, that featured a large choir of students, faculty, staff, and community members, and their performances of innovative repertoire included many premieres. Today there are frequent recitals in the chapel by students and visiting artists and a variety of concerts and symposia, even though the university no longer sponsors an active chapel music program.

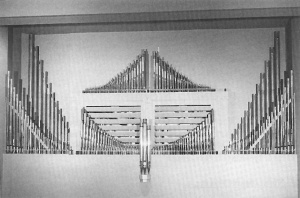

The organ in our own Hubbard Hall[3] is Aeolian-Skinner’s opus 1272, from 1952. At that time, of course, our building was the home of the Juilliard School of Music. The Hubbard Hall organ was obviously designed with studio teaching and practice in mind. The forward location across the front of the stage insures a clear line of sound, and the three manual and pedal divisions contain appropriate stops and ensembles for the convincing performance of a wide range of literature. This organ has gone through several stages of damage and repair, but as it stands it is essentially the same as it was conceived, and it represents a continuation of the Aeolian-Skinner tradition of placing instruments in major American conservatories. Aeolian-Skinner organs are also located in the Curtis Institute, Peabody Conservatory, the Eastman School of Music, and Westminster Choir College.

Aeolian-Skinner Organ, opus 1272, in Hubbard Hall, Manhattan School of Music (formerly Juilliard School of Music)

The organ in the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine is truly one of the great organs of the world. As opus 150, it was one of Ernest Skinner’s early successes dating from 1910, and much of what he did there, particularly the mechanism, remains unchanged to this day. In 1953 the organ was rebuilt by G. Donald Harrison as opus 150-A, and much of the old pipework was replaced.

At the time of the original organ, the nave had not yet been constructed. The vast space facilitated by the new nave, which opened in 1941, together with changing musical tastes necessitated a complete rethinking of the needs of the Cathedral organ. Its main function, in accordance with the purpose of English cathedral organs, was to accompany daily choral services, an activity requiring great flexibility and range of tone. It also had to have sufficient power to lead the occasional singing of a vast throng and to provide ceremonial effects inherent in the liturgy of so great a space.

Harrison drew on his past experience, repeating features from the design of the Liverpool Cathedral organ, which Willis had completed in 1924. Liverpool Cathedral is almost as large as St. John the Divine, and many unique techniques in scaling and voicing were used in both places. For example, the ranks of pipes are sometimes doubled or even tripled in the upper octaves to create a solid, even tone as the scale ascends. One of the most dramatic innovations is the installation of the State Trumpet on the west wall under the great rose window, some 500-plus feet from the main organ. This stop is voiced on extremely high wind pressure and it provides a telling presence for ceremonial occasions. The organ, although awaiting a major restoration[4], remains in its 1953 state, and it is a lasting monument to American organ-building at its best in the first half of the 20th century.

St. John the Divine has been the scene of many important events—religious, civic, and musical. Much of the organ music of Olivier Messiaen was heard there in its first American performances, and within a week of Messiaen’s death last May, Jon Gillock of the Juilliard faculty, who had been a student of Messiaen, played the complete Livre du Saint Sacrement as a memorial. There are weekly organ meditations /recitals on Sunday evening following Vespers at 7:00 p.m.

The organ in The Riverside Church is another story completely. It stands as one of the largest ever built by Aeolian-Skinner and is one of only four built by the company containing five manuals. (The other three are in the Mormon Tabernacle, St. Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue, and the Curtis Institute of Music.) the original organ for the new Rockefeller Church in 1930 was built by Hook & Hastings, a well-respected firm in the late 19th century. By all accounts, however, the organ was never a success, either tonally or mechanically. Virgil Fox, the popular, flamboyant virtuoso, was organist from 1946 to 1965, and he frequently fielded mechanical mishaps in imaginative ways which ensured that the full congregation of worshippers was made well aware of the organ’s inadequacies. The new five-manual console was built first in 1948 as opus 1118, and a complete new organ was finished in 1955 as opus 1118-B. Much of the design was dictated by Fox. As a result, the organ was not so much a monument to Harrison’s current thinking as it was to Fox’s lavish sense of the grand symphonic style, accented by his particular flair for the dramatic. The organ is unusually large and has gallery as well as chancel divisions. It also used portions of the old organ. While the Riverside organ incorporated Harrison’s basic concepts of the American Classic style throughout its divisions, it was first and foremost a “deluxe” church organ tailor-made to suit Fox’s dramatic style of service playing. Through his concerts, oratorio accompaniments, and recordings, the organ became famous.

In 1967 the organ received a major renovation, and several stops have been added since then, including visible pipework in the gallery. (Initially, church architects and officials had decreed that no pipework be visible in the church.) There are frequent recitals and musical events at the church throughout the year, and many of the world’s best-known organists have performed there. The past two organists of the church have been faculty members at MSM, and many of our students play their degree recitals there.

The chancel and a portion of the nave of The Riverside Church from an article in Life magazine, December 20, 1937.

It would be a mistake to suggest that these four organs are the most important in the city, but they do represent high watermarks in the history of a company that at one time was preeminent in the history of American organ-building.

For the intrepid organ-crawler, there are other interesting organs nearby. James Chapel of Union Theological Seminary houses a fairly new tracker action organ built by Holtkamp. An older Holtkamp is in Corpus Christi Roman Catholic Church on 121st Street. Also at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine are two two-manual Aeolian-Skinner organs in the side chapels, and there is a three-manual Ernest Skinner organ in the Synod Hall at 110th Street and Amsterdam Avenue (across from V & T Pizza). The organs in St. Michael’s Church at 99th Street and Amsterdam Avenue are arguably the best mechanical action organs in the city. A rather complete three-manual organ is located in the gallery and a small one-manual instrument is in the chapel. Both organs were built in the mid-1960s by Rudolf von Beckerath of Hamburg, Germany.

Incidentally, the chancel and chapel of St. Michael’s contain the most extensive array of appointments by Louis Tiffany in existence. Decorating schemes, windows, and mosaics throughout are executed by this renowned artist.

[1] In an email message to me dated April 14, 2012, Allen Kinzey, who worked for Aeolian-Skinner for many years, tells the exact scenario:

On January 2, 1932 the Aeolian Company and the Skinner Organ Company formed a new, third company called the Aeolian-Skinner Organ Company. Aeolian owned 40% of the stock in Aeolian-Skinner, and the Skinner Organ Company owned 60%.

Aeolian closed its operations in Garwood, New Jersey, and sent uncompleted contracts, the glue press, some material, and one employee (Frances Brown, who was a young lady then, and she worked for A-S to the end, or almost the end) to Aeolian-Skinner. The Skinner Organ Company deeded its property and turned over contracts, employees, materials, machinery, etc. to Aeolian-Skinner.

I assume Aeolian was hurt more by the depression as much of their work was residential. Therefore, they owned a lesser percent of Aeolian-Skinner. Skinner Organ Company continued on. Its sole purpose would have been as a holding company.

In Callahan’s The American Classic Organ [Richmond: OHS, 1990] on page 233 is a letter from GDH to Willis. I have always assumed that the third paragraph referred to buying out Aeolian’s stock. The $110,000 was about the value Aeolian put in its financial statement of its Aeolian-Skinner stock. “During the war —” would coincide with the 1943-44 ending of Aeolian’s listing of Aeolian-Skinner stock in its financial report and the end of Skinner Organ Company appearing in Moody’s. When Aeolian’s stock was purchased, there was no longer any purpose for Skinner Organ Company.

[2] An email from Allen Kinzey to me dated April 15, 2012, tells the exact work that was done on the organ as opus 985-B under the direction of Searle Wright:

Choir Organ

new 8 Flauto Dolce in place of 8 Dulciana

new 8 Flute Celeste tc in place of 8 Unda Maris

new 8 Viola from 4’C up with existing basses rescaled

revoice 8 Concert Flute 2’C up

new 4 Prestant in place of 4 Fugara

4 Musette = old Orchestral Oboe moved down an octave

Swell Organ

8 Aeoline = old Choir Dulciana in place of 8 Diapason

4 Fugara } = old Choir Fugara on new chest

2 2/3 Nazard } [tuned as a Nazard]

revoice 8 Hautbois

add 8 Vox Humana (Dome)

Brustwerk

new 8 Spitzgeigen in place of 8 Muted Viol

new 4 Montre on new chest

Pedal Organ

16 Montre } extension of Brustwerk 4 Montre

8 Montre } low 18 from existing facade pipes, rest new on new chest

add 16 Bombarde (Sw)

add 8 Solo Trumpet (Dome)

add 32 Bombarde } low 12 notes electronic

add 32 Bourdon } speakers located in the dome

Dome Organ – on Manual IV, enclosed (shades coupable to Swell and Choir shoes)

16 Solo Trumpet tc }

8 Solo Trumpet } new pipes on new chest

4 Solo Trumpet }

8 Vox Humana new pipes on new chest

Robert Turner built a new four-manual console which was installed in 1997.

[3] Now Greenfield Hall; the organ no longer exists.

[4] Quimby Pipe Organs of Warrensburg, Missouri, completed a major restoration in 2009.